Saltburn, Emerald Fennell‘s latest project after rape culture revenge comedy Promising Young Woman, is a riotous good time that thinks it’s giving “eat the rich” but isn’t, not really. It’d be one of my favourite films of the year if it wasn’t so thematically confused.

This searing satire is the epitome of “cinema is back” — it’s gorgeous visually, full of biting zingers mostly delivered by the iconic Rosamund Pike, and claden with cheeky symbolism that would make this a great film for HSC analysis if there wasn’t so much guzzling of body fluids.

Saltburn simply has to be watched on the big screen, if for no other reason than the fact that its scream-worthy squeamishness is best enjoyed in a packed theatre where the audience can all shriek in shock together.

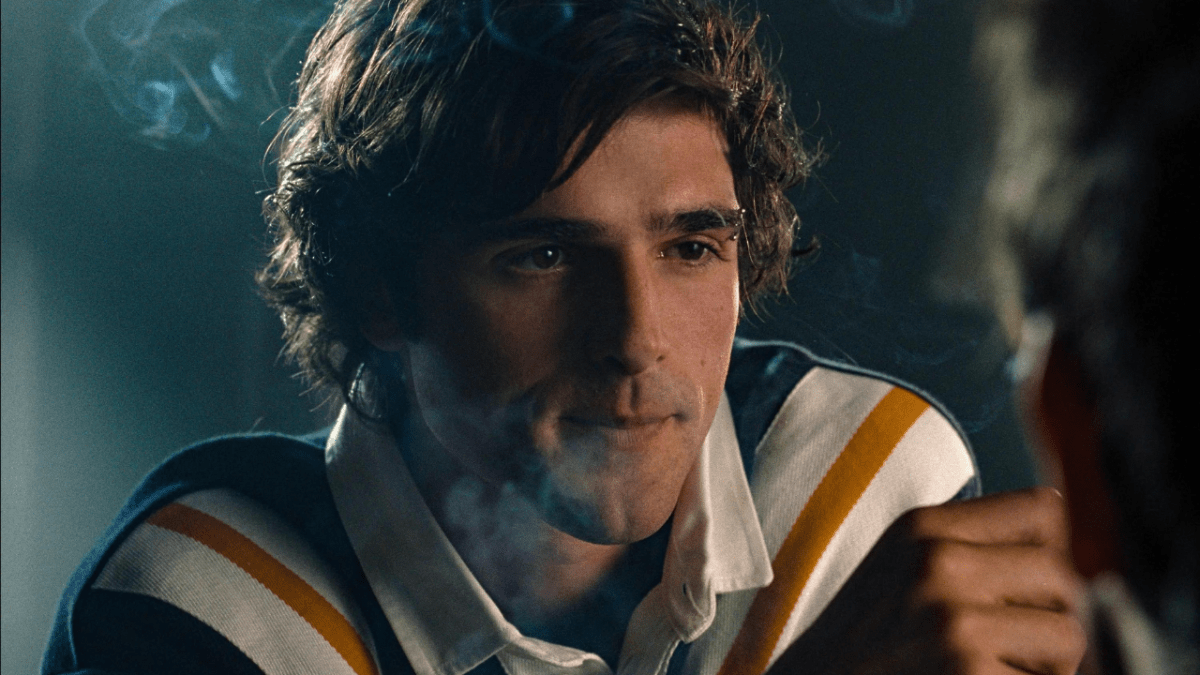

Paired with Jacob Elordi‘s truly magnetic performance as Felix Catton, and you have, as Harry Styles once put it, “a real, like, you know, ‘go to the theatre’ movie”.

Anyone who is yet to be converted into worshipping Elordi’s stardom will certainly be convinced by the end of this wild ride. He has that old Hollywood glamour and mysteriousness that makes me think we have the first real star of Gen Z on our hands.

But back to the film.

Saltburn follows the confusing, horny and ultimately doomed friendship between Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) and Felix Catton (Elordi), or at least it does initially. The film opens with Oliver monologuing about whether he loved or was in love with Felix, and his use of past-tense signals that something sinister has happened.

We go back to 2006 (yes, this film is a Y2K period piece) when Oliver is a painfully awkward scholarship student at Oxford, hopelessly pining after Felix who he either wants to be, or wants to be with, or both — we haven’t really figured it out yet.

Sexy, kind, compassionate Felix is the reigning god of the campus, and his power over the social order is attributed to his disarming sincerity. Through a seemingly lucky twist in events, Oliver is able to help Felix out with a dilemma, and in response, Felix entends his friendship and therefore social standing to Oliver, eventually inviting the poor boy back to his family estate Saltburn for the summer.

Whispers of a potential habit Felix has of bringing home strays and his casually cruel family’s vampiric delight at Oliver’s presence all serve equal bits dread and excitement as we wait for it to fall apart.

And it does, magnificently, devastatingly, in the centre of the family’s maze — a beautiful nod to the layered and confusing nature of these relationships in the first place, and a hint at what’s to come.

If Fennell had learned anything from the issues with Promising Young Woman, the film would have ended soon after this development, when Oliver and Felix’s beautiful and indifferent mother Elsebeth (Pike) both agree that wealth, while glamorous, is ultimately shallow. In a film about desire and what it can drive someone to do, this ending — while perhaps a little cliche — makes sense.

But, in what I’m starting to realise is a pattern here, Fennell cannot let questions go unanswered or allow ambiguity to leave us wanting more. She can’t allow us to have such a simple end to such a spectacular film, and insists on showing us how clever she can be by dragging the film out, transforming it from a psychosexual thriller to a rather garish spectacle that loses its meaning along the way.

Sure the rest is still very fun, but in the words of New Yorker‘s Richard Brody: “There are, in effect, two movies at work in Saltburn — the one that Fennell puts onto the screen and the one that it implies — and the implied movie is better.”

Saltburn ending, explained

WARNING: Saltburn spoilers ahead.

There are a few key moments in Saltburn that might leave viewers confused and, sadly, almost all of them are over-explained in a wobbly ending that shows Fennell doesn’t know when to take a step back and let the audience ruminate.

Felix is found dead with a bottle in his hand in the centre of the family’s maze the night he and Oliver have their disastrous falling out, and we wonder: did Oliver kill him? We suspect so, despite Oliver’s snivelling tears and devastation at the loss of the man he adored, despite the stunning scene in which we witness him having sex with Felix’s grave in a crescendo of desire and grief. Because that’s the point — that Oliver, needy as he is, desires. Desires Felix, desires what Felix has, who he is, what he represents. It’s this carnal, insatiable desire that the film, at least initially, appears to be critiquing — how the denial of desires leads to destruction. This is its “eat(ing out) the rich” moment. Until it isn’t.

Because the ending of Saltburn sees us go back in time to find out that all the films’ most shocking developments were meticulously planned. Somehow, this tense, erotic thriller about desire turns into a tacky whodunnit about a serial killer.

It turns out Oliver is more sociopathic than psychopathic — the death of Felix and the suicide of his sister Venetia (Alison Oliver) are not the spontaneous result of rejection and rage. Instead, the whole thing has been part of Oliver’s overly crafted plan to secure himself the Saltburn estate, which he does by killing all its inhabitants in a ham-fisted approach at a story which would have benefitted from more subtlety.

This goal of Oliver’s to become the elite undermines the sardonic satire’s messy attempt at class commentary. Sure, it pokes fun at the pish posh peevishness of the residents of Saltburn and their elite society, but poor and working class people are not even in the film — Oliver himself is from a middle class white family that goes on yearly international holidays and seems pretty well off.

The film also handles its race themes clumsily. There’s only one person of colour in this movie, Felix’s cousin Farleigh (Archie Madekwe), and only one line that even vaguely references the inherent ties between race and class — which is pretty quickly brushed off because the person who says it is such an ass.

The implication that Oliver’s motives are complicated (a confused lust for power and sex with someone unattainable), and then the confirmation that they are actually rather boring (sociopathy and riches), means it feels like this film is caught between two different movies, and it can’t decide which to be.

If only it ended 20 or 30 minutes earlier, and left us able to project our own readings onto it. Instead, Fennell has to have the last word, and the movie is poorer for it.