The unfolding videos from Burning Man look pretty familiar to Australian festival-goers.

For those who attended last year’s Splendour In The Mud, the flooded campsites and plastic-bagged shoes being worn in a desert in Nevada are hitting a little too close to home.

Despite being in different hemispheres, the experience for those at Burning Man and last year’s Splendour have considerable comparisons and raise the question: is this the new normal? Is this the future of music festivals in the midst of a climate crisis?

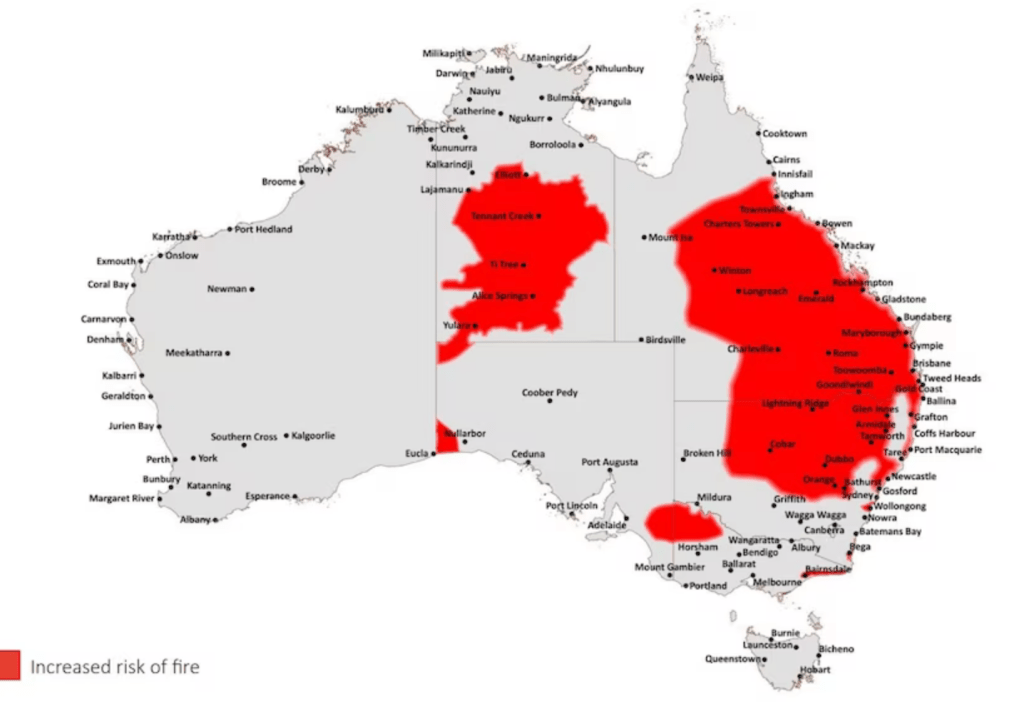

Australia has just experienced its hottest winter on record since records began in 1910. We’ve been warned of a looming extreme bushfire season that could resemble the devastation seen by the Black Summer bushfires.

On the flip side, we’re also about to experience the best summer of music since the pandemic. We’re seeing big artists return to our shores with stacked festival line-ups like Listen Out, Meredith and Lost Paradise.

SXSW is setting up shop and there are so many incredible side-shows that it’s going to be near impossible to see everything.

But this excitement and anticipation is underscored by a cautionary fear: the climate.

Over the New Year period festivals such as Lost Paradise and Beyond The Valley will host thousands of Australians dancing in 2024.

The Lost Paradise campsite is nestled in the beautiful Glenworth Valley on the Central Coast of NSW, a spot that The Australasian Fire Authorities Council have just put on their list of increased fire risk for spring.

This isn’t a new concern. In 2019 the Victorian leg of Falls Festival saw attendees get sent home one day into the festival due to an extreme fire risk.

The Falls organisers felt it was far too dangerous to continue with the three additional days, and looking at the risk on paper that decision makes perfect sense.

Imagine festival congestion of thousands of people on a campsite surrounded by bushland with 40-degree temperatures. Then add a bushfire to the mix and there’s no doubt it could have been catastrophic.

Last year Splendour In The Grass, Grapevine Gathering, Yours and Owls and Strawberry Fields were either partly or fully cancelled because of flooding and heavy rain.

The trauma of last years’ Splendour In The Mud may have contributed to ticket sales dropping by 30 per cent this year. The turbulent climate can make audiences hesitant to buy a ticket, not knowing what weather they’ll cop. The ecosystem of running an Australian festival is already pretty precious and now climate change will only make it more financially tough.

The Australian Festival Association undertakes risk assessments at the end of each year to identify potential risks for festivals both domestically and internationally.

They’ve identified climate change as one of the biggest risks to the industry from heatwaves and bushfires in summer, to flooding and severe rain in winter.

Extreme weather across seasons in conjunction with the pandemic has meant insurance has become far more expensive and in some instances actually impossible for organisers to obtain. Insurance premiums for Australian festivals have skyrocketed by as much as 300% over the past few years.

It would be unsurprising if many of the sites that have been used for years are soon given up for new spots with better evacuation routes, drainage and bushfire protection – both for financial longevity and safety of patrons.

What the future of our festivals will look like is a conversation that will continue between organisers, industry groups and governments. The most likely outcome will be new homes for our beloved events, and it’s already happening.

Despite criticisms that this year’s Laneway Festival lacked charm by moving away from its home at Callan Park, the practical provisions of being held at Sydney’s showground were a godsend.

The exhibition halls provided a reprieve from the heat, and even though the kilometres of concrete probably contributed to a microclimate, having a place to shelter from the elements would have drastically reduced the number of people falling unwell because of the heat.

Indoor festivals won’t be a silver bullet to this multi-faced problem, but it’s an interesting place to start when it comes to the shifting nature of festivals in Australia and abroad.

In the meantime we’ve got a few more years of getting sunburnt, soaked and muddy before we find new homes and solutions for our music festivals.