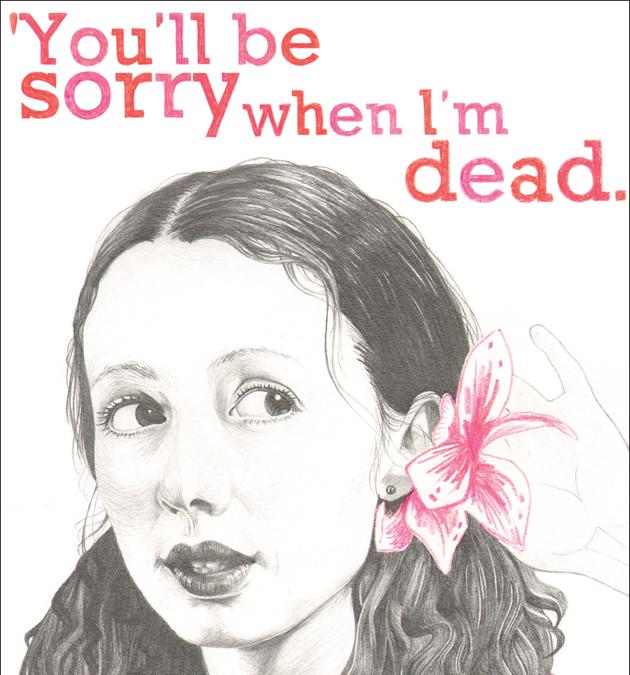

“At the age of eleven I decided with no small sense of certainty,” Marieke Hardy’s memoir begins, “that when I grew up I wanted to become a prostitute.”

She has hardly been a writer known for her reticence. Hardy made her name through unflinching candour, as readers of her award-winning (though no longer updated) blog, Reasons You Will Hate Me and her personal essays published in Frankie magazine and The Age will know.

You’ll Be Sorry When I’m Dead is a collection of stories as often ribald as it is hedonistic and funny – carrying us along at a terrific clip – like anyone familiar with her public persona would expect. But Hardy also takes her readers to far more difficult places – territory hinted at in the episodes of the ABC’s blackly funny LAID which she wrote last year, picking at the vagaries of youth and the debris of your own very recent past.

Over 295 pages she grapples with the sometimes irresistible pull of untenable relationships; with staring down the possibility of a friend’s death long before you should have to; and with facing the likelihood that when (or if) you should meet your heroes, you need to prepare for the horrible chance that they might also be human, and so, they might let you down.

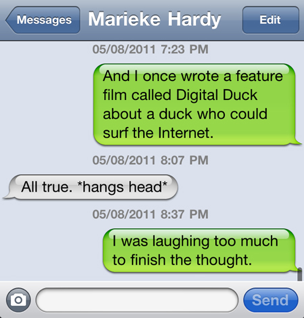

However You’ll Be Sorry also manages also to be really, very stupid-funny, quite a lot of the time. “This is one of the most intensely obnoxious sentences I have ever written in my life,” Hardy recalls in a chapter detailing her dark past as a person who diligently wrote letters to companies like the unfortunately singled-out cranberry juice maker Ocean Spray. “And I once wrote a feature film called Digital Duck, about a duck who could surf the internet.”

Hardy’s book might also, at times, just about break your heart. “As a creative person you take the stories of your life and sift through them,” she tells Pedestrian, “the only way you know how.”

This interview was conducted mainly via Facebook, a little bit over email, and just one time by text message.

ELMO KEEP: On a scale of one to ten, with one being Buffy the Vampire Slayer and ten being the Hostel series, how scared were you about writing a memoir before you started it?

MARIEKE HARDY: Not scared at all, surprisingly. Because I am an idiot and I probably thought to myself: ‘Oh, what fun. It’ll be just like one of my lightweight columns, only slightly longer.’ I knew for a while I wanted to write something along the lines of autobiographical humour-based essays (that’s the genre I aspire to, y’see) but wanted a theme to draw it together. I really like the ‘right of reply’ device, (at the end of certain chapters, the subject of the story is given pages in which to respond) as difficult as it was for me to read at times.

So, maybe as scared as that episode of Buffy where no one can speak? Anyway! How scared are you now that it is out?

I don’t know if I’m scared of people knowing the stories. I think they’re relatively amusing anecdotes. I was worried mostly about the reactions of those closest to me – my ex boyfriend, my folks, my best friend – but so far they’ve all been fine. I suppose I should wait ’til Christmas when they poison my tofurkey.

How much, if at all, did you censor yourself?

Not really much at all. Obviously at times I’ve gone for humour rather than searing ‘woe is me’ prose, but the stories are all there and real. I did have someone ask to be taken out of a story and I complied. Surprising as it may be, I’m not really looking to lose friendships over this book.

There’s lots of things at work when writers chooses to write memoir: part making sense of what’s happened in your life, part your own personal myth-making, part making the space for the reader to be able to relate to a story (and obviously sometimes completely other things, too, but for me these are that seem to apply most to you). You spent a while on your blog as a kind of agony aunt/advice columnist, so you obviously enjoyed having that connection with readers. How much of writing your book was about just sort of saying, “Well, everyone is muddling through life, doing the best they can?”

Oh, so much of it. So, so much. I’m completely obsessed with writers/artists like Aline Crumb, who just seem to vomit themselves helplessly all over the page. That she presents a side to herself that is so raw and vulnerable and human means as a reader you can’t help but feel comforted in some way. At least I do. I love wading through libraries full of drunks and whores and fuck-ups. I may not have urinated on myself like professional ex-drunk Donald Newlove, but I can certainly relate to some of his blacker, more anxious periods. I don’t mind presenting myself as a boorish, ill-mannered buffoon.

Who are some of your favourite writers in that field, of the autobiographical humour-based essay?

As previously mentioned, it’s hard to go past Bob and Aline. And David Sedaris is an obvious inspiration. When I was writing my stories I had with me at all times Helen Garner’s True Stories, Sarah Silverman’s The Bedwetter, and Martin Amis’ Experience. I’d like to think that I’m what would happen if those three people got drunk on cheap hooch and had a baby.

Though, I think to say your stuff is always humour-based is a bit of a misnomer: about two-thirds of the way through your book, you take it in a very not-funny and in fact heartbreaking direction. Do you feel like it’s hard to just go straight in and be vulnerable, like you wanted to spend time making us laugh first?

In terms of the vulnerability, I don’t think I consciously decided to pull people in with the ha-ha and then keep the sad stuff for later. I think there are moments of vulnerability in a lot of the stories. I certainly wanted to extend myself emotionally past the glib tone of my previous column work.

But you certainly did, also, make us laugh. I laughed out loud reading it, a lot. Especially re: Digital Duck, a film you insist that you wrote, and which sadly never saw the light of day. It is really a very sad story, actually. I’m sure it would have been amazing.

Christ, you are the second person to bring up Digital Duck as a favourite bit. Firstly: it is entirely true. I still have the script lying around somewhere. Secondly: It was not – sad to say – my original idea. I was commissioned to write the screenplay. I still can’t believe it wasn’t made. THE DUCK COULD TYPE ON THE KEYBOARD USING HIS LITTLE BILL.

These movie people are crazy! Also, my other favourite part is a wonderful story about you nearly being killed by birds as a tiny child in Trafalgar Square, (which I won’t ruin for everyone because it is so delightfully hilarious.) Deciding on the ordering of chapters in a book of essays must be a little like sequencing an album. Did that take a long time to do? Or not? If not, how pleasant!

That was mostly my editor’s doing, bless her. I didn’t really have a sense of chronology and just wrote the pieces as they came to me. I think there may even be some doubling up in certain stories (somebody told me it sounded like I was married twice as I’d referenced my wedding in two separate stories without a connection). She went through and tried to clarify who appeared first where, and when they appeared again. It’s not a traditional memoir by any means and I never intended it to be so. To me the stories can be read in any order, at any time, in any place. In the bath might be nice.

You write across a lot of different genres: opinion, personal essay, screenwriting. Which different parts of yourself do each of these satisfy and which do you most enjoy?

I think I need them all to keep me ‘balanced’, or as balanced as I’ll ever end up being. If I focused on just one I’d go batshit crazy, which is why writing the book was a royal pain in the arse. I wanted so much to just shift seamlessly between work, but the book demanded my full attention, the little cocksmoker. I love working in different fields because it means that if I have writer’s block with a script I can work on a column, or a blog, or so forth. And if all else fails I’ll just trade lazy bon mots on Twitter until I have the energy to write something halfway decent again.

Who read this book before it was published, other than the people who were in it? What makes you trust that person/people as editors/sounding boards?

My friend Ronnie Scott, who edits The Lifted Brow, gave it a once-over and bestowed some great wisdom upon it. Ronnie has an excellent eye and I knew he’d be able to pick up any glaring errors or holes in the ‘plot’ I’d completely missed. Everyone at Allen and Unwin was great too, though whenever they told me they liked it I thought they were just lying to me to make me feel better. I still suspect that.

What this book really seems like to me, is a love letter to the people in your life. To leave behind a proof that these people were here, they existed and lived. That it was a very deliberate decision to use real names (your dad even addresses this often problematic notion in the prologue). Is that what it is?

That is such a beautiful way of putting it. I may steal that. My dad still complains that I seem unable to cast a thin veil of fiction over my stories, but I just don’t know how to write any other way. I prefer truth in stories, even if that truth is occasionally jollied up for humorous purposes. There are certainly those in the book who would prefer I took my ‘love letters’ and shoved them where the sun don’t shine, but I’m hoping they calm down eventually. As a creative person you take the stories of your life and sift through them the only way you know how. My ex partner is a songwriter and when we broke up he wrote a few songs about our relationship. I felt uncomfortable on occasion when listening to them, but they were beautiful songs and he had every right to deal with our stories the way he wanted. That’s the way I look at the book.

You don’t address it super-directly in the book, but I wanted to ask you about the burden of expectation that comes with being part of a literary line.

I try not to think about it or refer to it too much. Frank was a political writer and our styles and careers are completely different. I’ve been working for long enough now that people have an idea of what I do and if they like it or not. I don’t feel I have to write something along the lines of Power Without Glory to fulfill some sort of family destiny. I’m happy to be a Hardy, but there are no expectations internally as far as I’m aware. You might have to ask my poor parents.

What is the writer’s ultimate goal, in your eyes?

To hold hands with their reader.

+

Marieke Hardy is an author, columnist and screenwriter living in Melbourne, currently at work on the second series of ABC 1’s LAID. Elmo Keep is a writer living in Sydney in a house where Marieke Hardy once stayed for a while with her dog, Bob Ellis. She last wrote for Pedestrian about the Cure.

Below is part one of an edited five-part extract from You’ll Be Sorry When I’m Dead by Marieke Hardy (Allen & Unwin, $29.99, available at all good bookstores from August 29).

I get the private message on Facebook, of course, of course. The technological town crier of my generation heralds news of births and mourns deaths and rings the bells of change to the point where a day without some kind of electronic revelation seems almost disappointing.

‘I’m hoping you may be able to solve one of the greatest mysteries of my lifetime so far.’

This is an intriguing beginning to a message. No less significant is the fact it seems free from subsequent pleas for the transferring of money to Nigerian ‘benk’ accounts or the bone-chilling sentence ‘So that’s about when I realised we had the same father.’

The message is from a friend I was glued to long ago. The word ‘glued’ undervalues the semi-psychotic devotion of our friendship. Susan and I practically lived inside each other. We spent every day together from 1986 to 1988 with a love nothing less than religious. The friendships of prepubescence invite no lighthearted commitment. You embody each other’s skin. Physically you may look nothing alike but elderly relatives insist they can’t tell you apart, and you enter rooms clutching each other around the waist or neck with a fierce sense of ownership.

‘I’m hoping you may be able to solve one of the greatest mysteries of my lifetime so far.’

Immediately I know I’ve done something wrong, been involved somehow. Was I part of some rape cover-up, standing around like a beer-swilling accomplice in The Accused? ‘One of the greatest mysteries of my lifetime so far’ sounds deeply important.

People like to make jokes about their forgetfulness. ‘I’m so darned . . . absent-minded!’ they exclaim with adorable shrugs, which can make memory loss sound very sweet and endearing though in my experience there’s very little endearing about standing bewilderedly in the middle of a living-room shouting ‘WHAT THE FUCK AM I SUPPOSED TO BE DOING IN HERE??’ particularly if it’s the living room of a complete stranger and you have wandered in wild-eyed off the street like Robert Downey Jr.

Yes, everybody sometimes forgets their keys, or the name of their boss’s wife (‘Oh god, I think I called her Sandra. Wasn’t Sandra the name of his second wife? I am totally getting fired on Monday’), or the easy-to-neglect fact that if you leave hot oil on the stove you will very probably burn your house down. A small amount of memory loss is normal. Spend an hour trying to remember where your car is parked at Chadstone Shopping Centre, fine. Sit up with a horrified gasp at 3 am realising that not only have you forgotten your mother’s birthday but you were supposed to bake the cake, understandable. A small amount of memory loss is daffy and darling and a defining character trait for girls who stick pencils in their hair or use phrases like ‘aw, baloney’.

My memory loss ranges somewhere between ‘oh dear, I seem to have left the house without any pants on again’ and Mickey Rooney, a man who, if his fake Twitter account is to be believed, spends his downtime asking questions like ‘Why am I eating this cake? Why am I wearing a party hat? Why are people singing at me?’ and ‘What’s a volcano? Can I have two soft tacos? What’s a taco?’ Why anyone would look to me for answers requiring a delve down memory lane is beyond comprehension. And yet here she was, after twenty years, my Susan.

http://www.mariekehardy.com

http://www.allenandunwin.com

Lead image by Cybele Malinowski