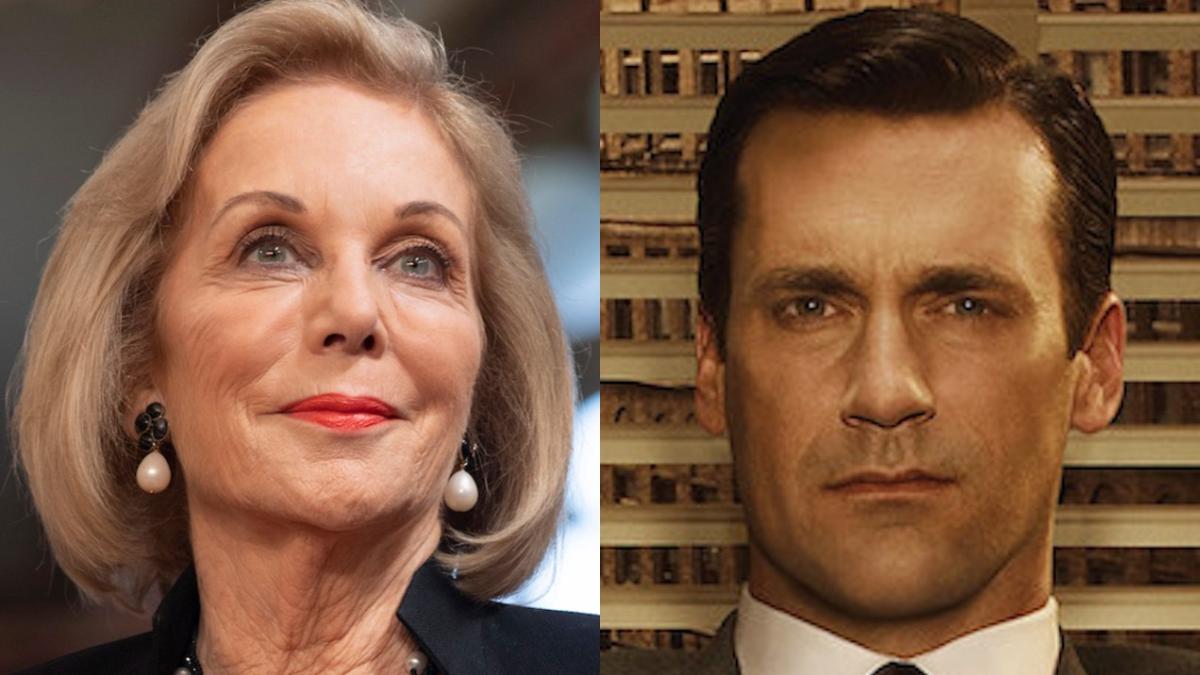

There’s a scene in Mad Men which has rattled around my head for years. Peggy Olson, a junior copywriter at a top New York City advertising agency, strides into the office of her boss, Don Draper. It’s after hours, and Peggy pours a drink at Don’s bar cart, an accoutrement we’re led to believe was an office staple circa 1960.

She reveals she just broke up with her boyfriend, but is ready to settle down for a long night on the tools. Don tells her to go home. Peggy baulks, suggesting that he made the mistake which forced her to stay back in the first place.

The pair fight, with Peggy eventually accusing Don of stealing one of her ideas for a successful campaign.

“That’s your job,” Don says, lit cigarette still in hand. “I give you money, you give me ideas.”

“You never say thank you,” Peggy replies.

“That’s what the money is for,” Don shoots back, adding that Peggy should be “thanking me every morning when you wake up, along with Jesus, for giving you another day.”

Peggy leaves the room as quickly as she entered, leaving Don to process the kind of workplace dispute which, unlike her pillbox hat or his indoor smoking, never quite faded into obsolescence.

The scene nudged into my consciousness when I caught today’s Sydney Morning Herald report on recent comments from ABC chair Ita Buttrose, who used a behind-closed-doors meeting to outline the differences between her generation – Peggy’s generation – and Millennials, the catch-all demographic for anyone between 22-ish to 38-ish.

“What does change is the expectations of staff, that’s where the change occurs,” Buttrose is reported to have said, claiming she relished a lack of communication with the big-time media bosses of her youth.

“But it seems to me that today’s younger workers, they need much more reassurance and they need to be thanked, which is something many companies don’t do,” she added.

I am hardly a pioneer in the Australian media, as Buttrose is, nor am I an under-appreciated genius, like Peggy. I won’t even pretend I’ve personally had a hard go of it, as men who match my physical and cultural description have been ushered into the local press since there was a press.

I do fall into the Millennial bracket, though, which means I can suss how some things have changed since Buttrose first landed an entry-level job at a magazine at age 15.

The fact Buttrose even started as a teen speaks to a different media ecosystem entirely; while I won’t deny the grit needed to slash through the dense undergrowth of private schoolboys guarding the press, today’s schoolboys are university-educated, too.

The industry has become professionalised to a point where degrees are all-but required to even have a sniff at those entry-level positions, to the detriment of young, talented writers who can’t spend three years and $30,000 on a journalism degree.

Scratch that: $45,000 for a degree, if the Federal Government’s changes to university funding rumble into action.

And what of the industry Buttrose navigated? Much of it no longer exists. Cleo, the magazine she founded in 1972, was shuttered by new owners Bauer Media in 2016. This week, Bauer took a hatchet to the remnants of an Australian magazine empire, confirming the closure of ELLE, Harper’s BAZAAR, and six other titles.

That’s to say nothing of newspapers, or, god forbid, digital media, those outlets which dared to imagine a new pathway for young journalists, only to be crushed by the weight of austerity and the coronavirus pandemic. The ABC last month confirmed bulk redundancies and a change in focus for ABC Life, its foray into digital-first content aimed at a young, diverse audience (Buttrose did rail against the funding cuts which led to that decision).

“They’re very keen on being thanked and they almost need hugging – that’s before COVID of course, we can’t hug any more – but they almost need hugging,” Buttrose said, claiming Millennials lack the “resilience” of older generations.

I am sorry for making you sit through another myopic media rant, but the truth is applicable elsewhere: More workers are fighting for fewer jobs, during a deadset industry maelstrom. Legions of young Australians are studying to work in a field which, more or less, doesn’t exist in the way it once did. From a great enough distance, I understand how ‘seeking reassurance’ may equate to ‘needing a hug’, how despondency at waves of job losses may feel like a dearth of ‘resilience’.

Australian comedian Ben Jenkins has a theory about Buttrose’s comments.

He suggested Buttrose’s commentary, and, by extension, the viewpoint of an entire class of successful elder figures, may be shaped by the concept that swallowing enough workplace bullshit is necessary for success, and that demanding better from those systems is a sign of weakness.

https://twitter.com/bencjenkins/status/1286105087362789376

I can’t speak to the mind of Buttrose, but I understand how someone who overcame previously insurmountable odds in her career may form some unique thoughts about resilience.

Peggy was resilient, for what it’s worth. After riding a carousel of bullshit, she rounds out Mad Men as an industry mainstay.

Don winds down the series by buckling to softness. The last scene shows him, eyes closed, meditating on a hilltop.