“Defund the police.” You’re hearing it more and more. In recent days, figures like John Legend, Lizzo, and Natalie Portman have reportedly thrown their weight behind calls to stop ballooning police budgets, with activists claiming it’s a matter of national urgency.

It’s not unusual for pop superstars and Hollywood legends call for peace, justice, and equality, but defunding the police is a hefty proposal.

So, what does it mean to defund the police, why are some folks calling for police departments to be scrapped, and what would those proposals even look like in Australia?

I personally think it’s really cool how we all went from learning how to make banana bread to learning how to abolish the police in a matter of weeks

— Asma Nizami (@asmaresists) June 6, 2020

What’s going on, then?

After the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis Police officer was broadcast around the world, the city’s council reached a stark consensus: the police department, and the system which led to an unarmed black man dying after the intervention of a white police officer, could not be reformed. With an overwhelming majority, the council moved to dismantle the organisation, pledging to replace it with a new model of community safety.

It was a landmark decision, and the city now has an extraordinary opportunity to reshape what it means to uphold safety, law, and order.

And how did we get here?

Associate Professor Justin Ready, from Griffith University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, says the extraordinary rebuke of the Minneapolis Police Department has been a long time coming.

While Floyd’s death was the trigger for mass civil unrest, Prof. Ready says other high-profile instances of racial injustice, and the nation’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, exposed which public services the US chooses to prioritise.

The people who most often brush up against the police are “people who need services, they need assistance,” Prof. Ready says.

This is where demands to defund the police come in.

Taxpayer funds for those community programs are often siphoned away by police departments, Prof. Ready says, pointing to the proliferation of military equipment in law enforcement.

Not only is it extremely expensive to provide police with weapons of war and highly-armoured vehicles, it sends a clear message: the police are not there to help, but to crush dissent.

“They can’t be treated like an enemy that needs to be defeated,” Prof. Ready says.

“But when you use military equipment, there is a general sense among the public, especially marginalised people in the inner city, that the police are like an occupying force.”

For what it’s worth, police in Australia have dabbled with hardcore firearms for a while now. In 2017, a number of NSW Police officers were handed semi-automatic assault rifles, and in March this year, NSW Police Minister David Elliott came under scrutiny after rattling off a few rounds from a submachine gun at a rifle range.

Yet the decision to end the Minneapolis Police Department goes beyond annual budgets. No weapons, military or otherwise, were used in the arrest of George Floyd; unlike a high-tech rifle, it costs nothing to apply a knee to a handcuffed man’s neck.

The City of Minneapolis hopes defunding and dismantling the police department will eradicate the system which led to Floyd’s death, potentially saving others from similar deaths in custody.

What about responses to violent crime, and cracking down on drugs?

MPD150, an organisation which proposed alternatives to the Minneapolis Police Department in a scathing 2017 report, believes there may be a need for a “small specialized class of public servants whose job it is to respond to violent crimes.”

So, police. But not cops as we know them; it would be a small unit to deal with the really bad stuff, like responding to domestic violence incidents or chasing down killers.

MPD150 argues that the vast array of roles currently handled by police forces around the world – such as dealing with people experiencing mental health issues, or responding to drug use – should be handled instead by community service experts. It’s a targeted, holistic response, not a one-size-fits-all outfit from cops who are armed to the teeth.

It is likely the city’s new community safety protocols will prioritise mental health services, and will bolster firefighting and paramedic services, limiting the number of armed officers called to intervene in non-violent situations.

As for the criminalisation of drug use, a big part of abolition is the idea that many things that are currently crimes, like many forms of recreational drug use, really shouldn’t be.

Instead of criminalising drug users, addiction support services should be used instead.

This is all “bigger than just police brutality,” MPD150 says.

“It’s about how the prison industrial complex, the drug war… and culture that forms our criminal justice system has destroyed millions of lives, and torn apart families.”

Back on the celebrity thing for a moment, Marvel superhero Simu Liu, who has thrown his weight behind the policy proposal, put it this way:

“WhAt WiLl We RePlAcE ThE pOLiCe WiTh?!?!”

Social Workers. Crisis staff trained in de-escalation. Womens’ shelters. Counsellors. Planned Parenthood. Therapists. Safe injection sites. Rehab. Community outreach. Night classes. Affordable health care. #ImagineSomethingDifferent

— Simu Liu (@SimuLiu) June 9, 2020

Right, so how is all of this going to happen?

We’re yet to see how the city’s new safety protocols will take shape, but Prof. Ready is circumspect on the need to abolish policing altogether: building relationships between police and the communities they serve, tougher applicant screening measures to pick out “bad apples”, and eliminating chokeholds are some of the reforms Prof. Ready thinks could make policing safer.

“The question is, what does Humpty Dumpty look like when you put him back together again, and is Humpty able to actually quell some civil unrest and create a sense of progress?” Prof. Ready says.

“I’m not sure about that.”

And what’s the situation in Australia?

The tragedy in Minneapolis coincides with a reckoning on home soil, and a renewed focus on the 437 Indigenous deaths known to have occurred in custody since 1991’s royal commission.

In the days since Floyd’s death, Australia has witnessed a NSW Police officer sweeping the legs of a 16-year-old Indigenous boy in Sydney. NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller said he believed the officer simply had a “bad day,” but the boy’s family claim the footage shows only a fraction of the police force used against Indigenous Australians every day.

Attention has returned to the death of David Dungay Jr, a Dunghutti man who died in 2015 after he was restrained by guards in Long Bay prison hospital. Like Floyd, he said “I can’t breathe” in the moments before his death.

And then there’s NSW Police use of pepper spray on protestors last weekend, to say nothing of the organisation’s continual use of invasive strip searches, which some politicians believe effectively amount to sexual assault.

These are some of the issues which drive Debbie Kilroy, a lawyer, founder of Sisters Inside, and a staunch advocate for police abolition in Australia.

Kilroy, whose organisation works to support women incarcerated in Australia, has long called for the abolition of prisons – and the systems which support them.

“This cycle is a direct continuation of colonisation,” Kilroy wrote in 2018 for the Griffith Review, pointing to a “recent wave of coronial inquests, inquiries and royal commissions [which have] done nothing to change the structural racism that is the bedrock of Australia’s criminal injustice system.”

Kilroy calls abolition an “imaginative” project, which “requires us to imagine a world where we do not rely on police, prisons and child protection authorities to resolve and address violence and harm in our communities.”

To imagine Australia without police is to imagine a society which first targets the causes of crime – poverty, addiction, and homelessness among them. It also requires a recentring of Indigenous Australia in public policy.

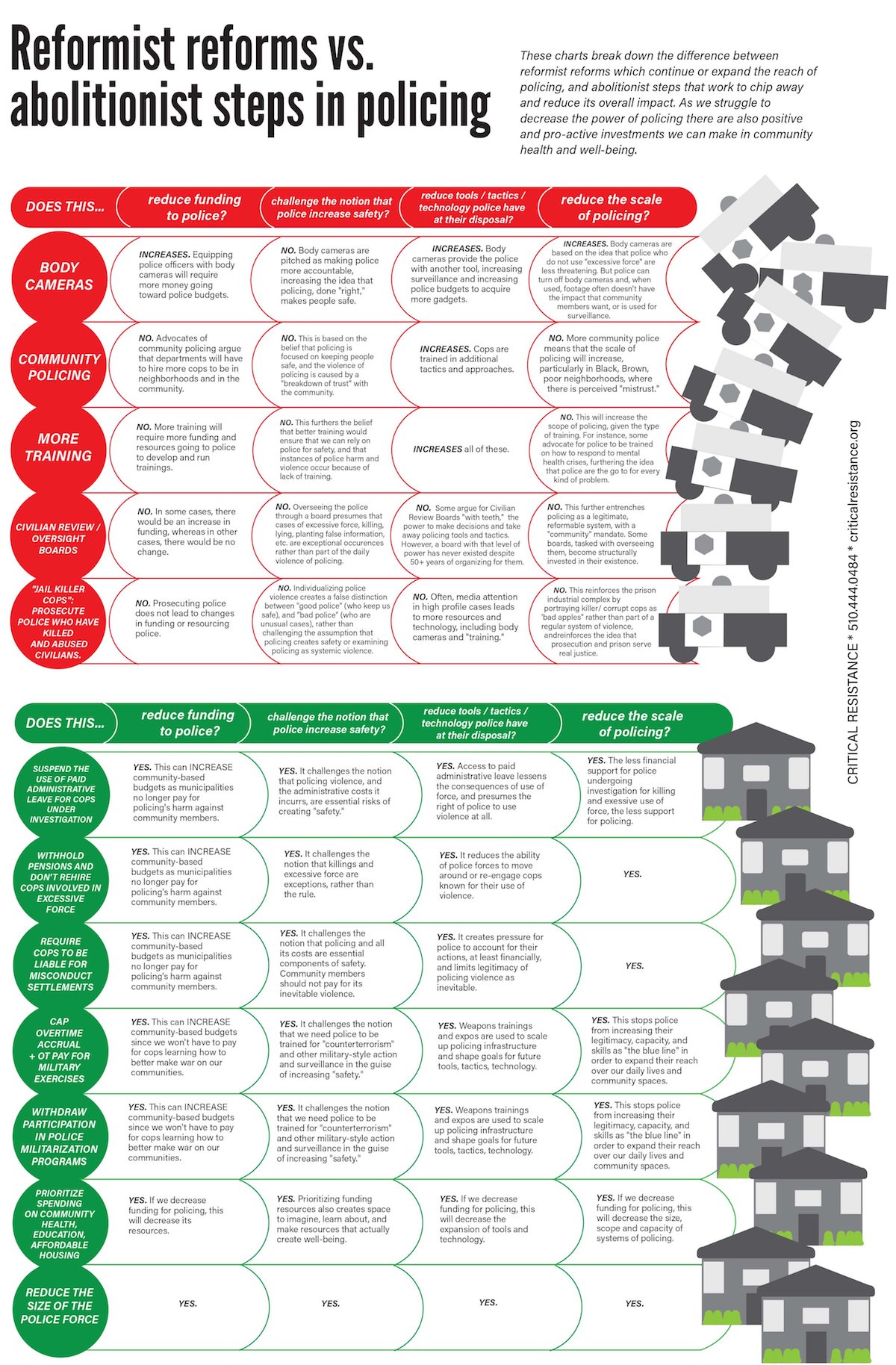

A chart of reforms, boosted by Kilroy in recent days, hints at what changes could be made in the service of abolition, including a prioritisation of public spending on housing and health services, ending paid administrative leave for police accused of wrongdoing, and, quite simply, cutting the number of officers on duty.

Prof. Ready, whose research has primarily focused on American policing, said it’s impossible to tell whether reforms could permanently uproot biases in Australian policing.

“Can we ever eliminate racial injustice in Australian policing? Really tough question,” he says.

“I don’t know. I mean, there’s always bias there, isn’t there.”

There’s a long way to go before we see real change in Minneapolis, let alone Australia.

But to abolitionists, defunding the police feels like a tangible way to stop entrenched biases from causing further harm.