Remember Juukan Gorge?

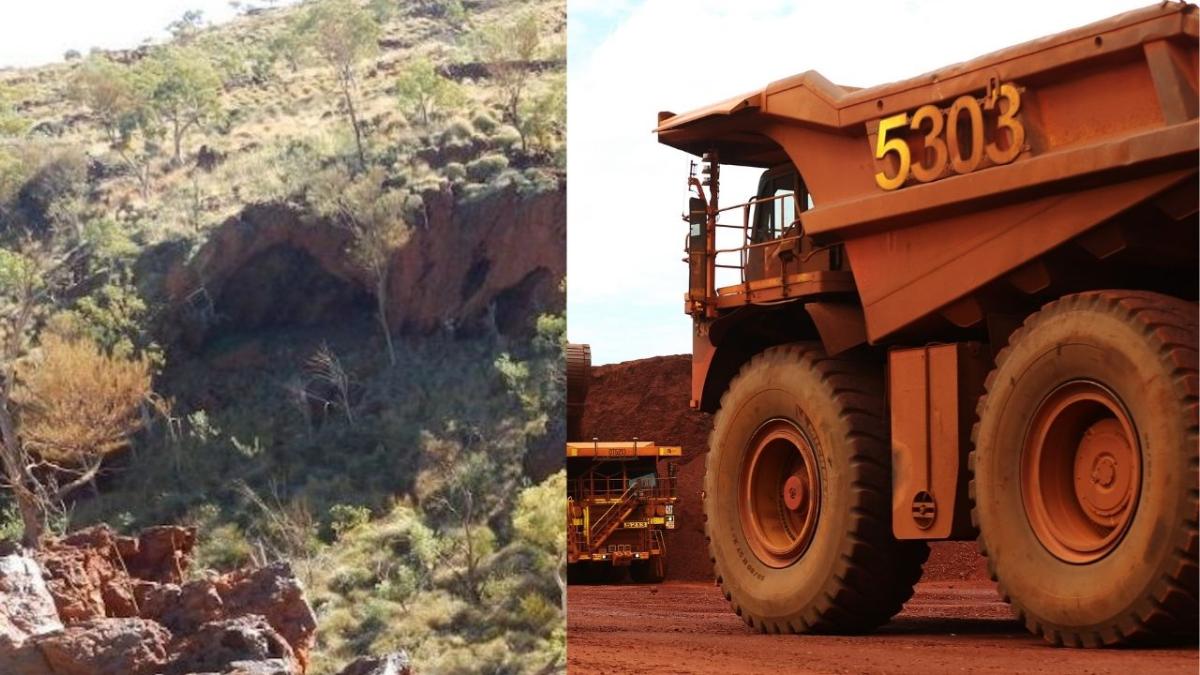

In case you’ve forgotten, it was one of the absolute worst things about 2020, which is saying something. Last year, Rio Tinto blew up a 47,000-year-old cultural site of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people in the Pilbara, in north-west WA.

Rio Tinto destroyed one of the oldest sites of human civilisation. It was 10 times older than the Pyramids in Egypt.

The destruction was condemned by the United Nations, forced a round of resignations at Rio, and shone a light on the laws supposed to stop things like this from happening. Parliament even established a Senate inquiry to investigate how governments could prevent another disaster like Juukan.

The destruction isn’t confined to WA – in every corner of this country, Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities are facing off against the desecration of cultural heritage and sacred sites. In NSW alone, over 400 applications to impact or harm Aboriginal heritage sites have been approved by the state government since 2016 – an approval rate of 100%.

This week, that inquiry published its final report. It recommended massive changes to the laws that give resource corporations nearly unlimited power to mine, drill and blast Aboriginal sacred sites and places of cultural significance – even if local Traditional Owners don’t want them there.

It’s a massive opportunity to advance Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Rights in a way we haven’t seen for decades. But the mining and fracking industries have already warned that they’re going to fight tooth and nail to stop the law from changing.

This is big. Beyond big. Because right now, the system is unbelievably broken. I know because I’ve seen it close-up.

How big business undermines Native Title

Every six months or so, I get a call, or an email, or a message on social media. It’s a corporate headhunter working for one of the big mining or gas corporations, and they want to offer me a job.

On paper, these jobs sound pretty good. Unbelievable salaries. Impressive titles. Cushy perks. And all I’d have to do is what I do now — go out to Aboriginal communities across the country, and talk to people.

At the moment, I travel to these communities to listen. Everywhere I go — the Beetaloo and McArthur Basins in the NT, the Pilbara — people tell me the same things. They’re scared, upset, and confused.

A mining or gas corporation has announced plans to drill on their Country. They’re worried about what fracking will do to the water and country. They’re worried about their sacred sites being destroyed. They’ve heard horror stories from other places where fracking has poisoned the ground, or where mining has blown up sacred sites.

The resources corporations want me to do something a bit different. They want me to go out to these communities and talk about what a wonderful opportunity mining or fracking is for the town.

About how all those news reports and studies of resources corporations destroying sacred sites and cultural heritage are things of the past. Juukan Gorge, Garnkiny, the Banjima rock shelters — those were one-time things.

Anyone who does work like mine has had job offers like these. It’s only part of a strategy that gas corporations have rolled out time and time again. For years, I’ve watched them do it in remote towns and communities all over Australia. They sow doubt, division and confusion, turn people against one another, and stroll through the wreckage to get what they want.

The dirty little secret is that these corporations don’t actually need a community’s consent to mine or frack on Aboriginal land. They just need the appearance of it. Even when a community is overwhelmingly against a mining or gas project, there’s almost nothing they can do to stop it. That’s because for decades, Native Title and cultural heritage protection laws have been white-anted and attacked by corporate interests.

Frack off

Take Origin Energy. Origin plans to frack an enormous, 18,500-square-kilometre section of the Beetaloo Basin. Despite a Senate inquiry finding “strong and widespread opposition to the shale gas industry” in the Beetaloo, Origin claims it has consent from Aboriginal communities to go ahead and start drilling.

On the ground, though, it’s a very different story. In an open letter addressed to federal politicians earlier this year, Traditional Owners across the NT said that gas corporations have “failed to follow proper process in consultation with us, failed to acquire consent, failed to provide transparency in their dealings with us, and have systematically excluded our voices from the decision-making process for activities on our Country”.

And that’s the real problem: any “consultation” that resources corporations do in Aboriginal communities is usually tokenistic, one-sided, or outright rigged. Of the family groups that have been granted exclusive Native Title rights by the federal government and live on the land Origin wants to frack, very few I’ve spoken to have even heard from Origin.

Our Native Title and cultural heritage laws were never made for projects at the massive scale that we’re seeing proposed with the fracking gas fields in the Northern Territory. Multiple clans, language groups, and enormous geographical areas can’t be accounted for under the current regime, effectively silencing Aboriginal people from protecting their homelands.

In many of the “consulting” sessions corporations like Origin run that I’ve sat in on, there haven’t been translators for people whose first language isn’t English. And Traditional Owners told the Senate inquiry that mining and fracking corporations regularly neglect to give people basic information they need to make informed decisions, like how many drilling wells will be sunk, or where they’ll be.

Which is why they want to hire people like me. They want a Black person they can wheel out whenever they need one. They want someone to say they’ve done “extensive consultation” with Traditional Owners, and that people in remote Aboriginal communities are on board with mining and fracking, apart from a few troublemakers.

This week, Origin held its Annual General Meeting over Zoom. A few of those troublemakers — Traditional Owners from across the Beetaloo — were on the call too, along with a number of Origin shareholders who weren’t happy with how the corporation has been doing things. [Editor’s note: Origin has released a statement about the Annual General Meeting.]

Some of those shareholders put up a resolution calling on Origin to “cease all operations” across the Beetaloo until Traditional Owners are given veto power over any planned drilling that would disrupt cultural heritage and sacred sites. That’s one of the biggest recommendations made by the Senate inquiry — the crazy idea that Aboriginal people should be allowed to stop mining or fracking on their own Country if they don’t consent to it.

The way Origin responded gave a pretty good idea of what they think “consultation” and “consent” looks like. When Aunty May August, an Alawa woman, tried to ask the Origin board a question, Origin responded by hanging up on her the first time she called. [Editor’s note: Origin dispute this.]

If Parliament gives Traditional Owners the power to veto mining and gas projects on their Country, that kind of “consultation” might soon be a thing of the past. Disasters like Juukan Gorge wouldn’t happen, and people would actually be held to account for them. I think that’d be a pretty amazing thing.

Enormous public support and pressure has gotten us this far. We are on the cusp of seeing land rights legislation introduced, like we haven’t seen for decades. It’s on all of us to make sure that this report isn’t relegated to a shelf to gather dust. We need to keep the pressure on the Government to legislate strong new laws to hand power to where it belongs — Traditional Owners.

Larissa Baldwin is a Widjabul Wia-bul woman from the Bundjalung Nations and First Nations Justice Campaign Director at GetUp