Cell 17 resembles most others at Old Melbourne Gaol. Three meters of stone floor separate four cold, brick walls. A barred window adorns one wall. Opposite, the door squeaks on its hinges, its heft explaining its purpose – keeping people inside. And it is very, very good at keeping people inside.

But our tour guide said Cell 17 is not like the other cells at all – that it is uniquely good at holding the spirits of former inmates. That this cramped, gloomy nook is the most haunted cell in Melbourne’s disused penitentiary.

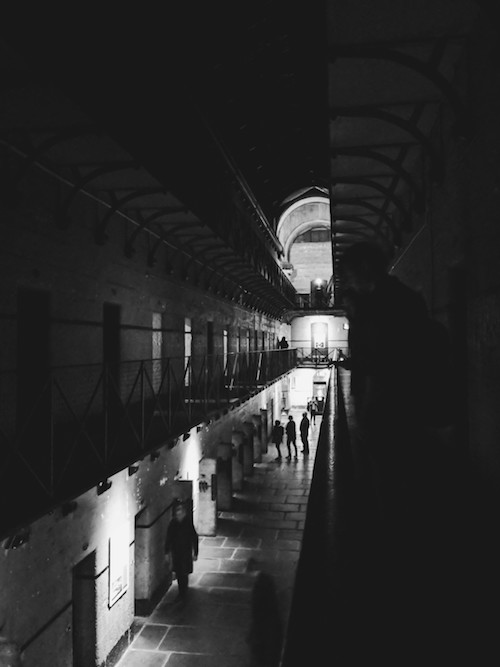

Along with two colleagues and a dozen other visitors on Old Melbourne Gaol’s Ghost Tour, I watched a volunteer step into Cell 17. The door closed with a thud, echoing down the cell block. We waited, shuffling our feet, imagining her terror. Secretly, I hoped the she would emerge wide-eyed, twitching, and utterly convinced she had shared Cell 17 with the restless dead.

The door swung open. I held my breath. She tiptoed out, faced the group, and announced that she hadn’t felt much of anything.

“Cell 17 on the second floor is an interesting one,” Sophie Hayes told me in the days after my visit.

A former volunteer who spent three years as a visitor guide, Hayes maintained Cell 17 was notorious among her colleagues for its supernatural energy.

“Highly trained seeing-eye dogs panicked in Cell 17,” she said, claiming they “started acting erratically, refused to enter and had to be taken outside to calm down.”

She recounted tales of camera footage being wiped within its walls, and the time a radio crew allegedly fled, terrified, when a spirit yanked a journo through the doorway.

It was hard to imagine after the spirit-less nature of my visit.

Not like I walked away from Cell 17 feeling cheated, mind you.

Old Melbourne Gaol sits at the north-eastern corner of the central business district, its bluestone walls defying the modern apartment blocks above. The state’s most dangerous criminals were locked inside, until its closure in 1924. So too were others on the fringe of the city’s exploding population: the homeless and the mentally ill were also swept into Port Phillip’s first dedicated penitentiary.

“Children as young as 10 could be sent there for committing crimes,” Hayes added, “While others came in with their convicted mother’s if they had nowhere else to go.

“Police even arrested a 4-year-old once who was found wandering on the street.”

Many of their names have been lost to time, but the legacy of Old Melbourne Gaol’s most famous inmate endures. The tour showcases the beam from which Ned Kelly was hung, and the trapdoor which saw the bandit fall to his death. Those artefacts, and the grisly tale which imbues them with history, are affecting. To stand in the dark, gazing at the lever which condemned many of the 135 convicts hung at the site, is to stare at one of the city’s most deadly relics.

Staring at the gallows, I wondered why there should even be a ghost tour when such concrete artefacts of death were right there; the feeling was compounded when our guide, a friendly gent with the calm, knowledgeable demeanour you’d hope for on a grim prison tour, produced photos of the supposed apparitions our group had managed to miss. Somehow, a smudge of light captured on an old iPod camera was less affecting than the menacing aura of everything else at the Gaol.

Maybe I’m too far gone, my disbelief too deeply entrenched, but those images didn’t stir anything in me. Nor did our guide’s stories of spiritually-attuned visitors being thrown off by the Gaol’s non-corporeal residents.

It wasn’t fear I felt in the Old Melbourne Gaol, and it wasn’t fear I left with, rather a grim recognisance of the building’s history and purpose. The cells are eerie, and retracing the steps of a condemned man up the stairway to the gallows is stirring, but only because the building harbours a genuine legacy of suffering. The threat of running into some spectral resident didn’t spook me as much as the idea of tumbling down those steps, becoming yet another visitor carried out of the building with a snapped neck.

“One of the creepiest things to me is that some of it is still unexplored,” Hayes said.

“When the Gaol was closed for use much of it was sealed up, and even though we only have one cell block left it still contains many mysteries.

“As recently as the 2000s, new areas were still being discovered, with an area behind a brick wall being uncovered and leading to a separate room which we believe was an entryway to the old isolation and punishment cells.”

That would be worth peering into on a silent, pitch black night.