What first took you to Sierra Leone and how has your experience changed in the last six or so months since the Ebola epidemic began?

I arrived in Freetown three years ago to work on a maternal health project providing free health care to mothers and children. I then started freelancing on various health projects, started a fashion blog and started my own small project supporting young athletes in Sierra Leone.

In the last six months my experience here, like everyone’s, has changed enormously because we are completely consumed by fighting Ebola. I work all the time and have little semblance of a life outside of the office. I don’t have much time for the stuff I used to enjoy doing, like chasing stylish people on the streets.

Can you tell us more about your current role in Sierra Leone?

I try to keep writing and blogging, but I am mostly focused on my day job working for [King’s College London] Sierra Leone Partnership, a health project based at the main teaching hospital in Freetown. King’s runs an 18 bed Ebola isolation ward and is helping to establish other Ebola wards across Freetown.

Above: Miniratu, a coordinator at the Freetown and Western Area Command Centre, wears her Sunday church ensemble to the office where she works seven days a week. Now that she doesn’t have time to pray in church, she does so at her house, where she “prays that this sickness will dissolve from our country, I pray that this will happen tomorrow.”

The spirit of the Sierra Leonean people comes across so readily in your photos. Has the atmosphere changed in Sierra Leone or are people still going about their everyday lives?

What’s unfolded here is utterly heartbreaking and life changing for so many people, however the resilience of Sierra Leoneans is inspirational. Ebola has served this country a terrible blow, but somehow the spirit of its people has not been broken. In many ways life goes on as usual and there are moments when you forget that you are living in an Ebola outbreak. But then you learn of someone (a friend of a friend or health worker you know or a colleague’s relative) who is infected, or you see a quarantined house, or an ambulance screams by with the drivers dressed in full PPE suits, or you sit in the hospital for a day, you are reminded that this thing is still here.

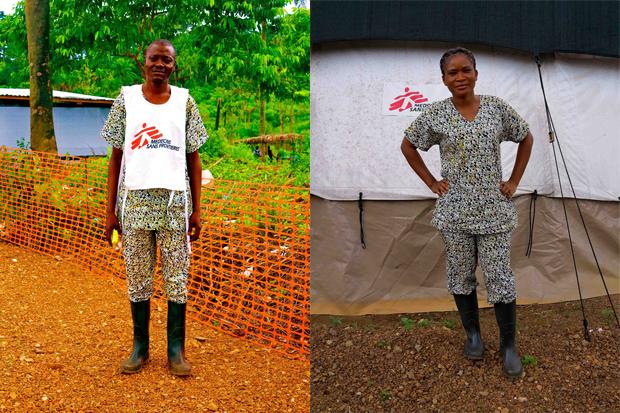

Tamba (L) and Mattu (R) are health promotion officers for MSF sporting custom scrubs. Says Tamba: “I didn’t know anything about Ebola before this outbreak. I used to be afraid of Ebola and I even refused to come to this hospital. But now I know more than anyone about Ebola, ask me anything and I can tell you. We teach the patients about the disease, I love my job.”

Do you have fears for yourself in regards to catching Ebola?

Not really. You have to think about it rationally otherwise the fear could destroy you. I think when the outbreak started I felt a lot more vulnerable, but now I’m more aware of who is likely to be infected. When you work with doctors and nurses who spend time on Ebola wards you realise they are the people to be worried for. I take basic precautions, like using chlorine to wash my hands. I also live a relatively protected life compared to most people in the country – it is the poorest communities who are most vulnerable to this disease.

How would you rate the international response on the ground? Does it feel as if the international community is doing everything they can or is there still a long way to go in regards to providing resources and support?

The international response has been extremely sluggish. Five months ago when huge case numbers were emerging in remote communities in the east of the country, nobody was interested. The Government was slow to respond and an already fractured health system allowed the disease to spread quickly. It was also assumed that the outbreak would be contained like in previous outbreaks in Uganda and DRC. The few international organisations that remained on the ground like MSF and Red Cross and King’s have been pleading for help since July. But the international response was not properly stepped up until Ebola started knocking on the door of the US and UK.

Retired policeman and father of four John Mansaray collects mosquito nets courtesy of UNICEF to ward off malaria – the biggest killer of children under the age of five in Sierra Leone.

Do you feel the picture that the international media is painting of the situation is accurate?

There has been some great reporting that gives you a balanced view of what is happening. I’ve read some fascinating stories, particularly around health care workers and survivors. But a lot of mainstream media chooses to paint a hysterical picture of the situation. The recent coverage of Ebola in America was outrageous and really shifts the story away from where the heart of the problem is and where a response is needed. Sadly there is a lack of Sierra Leonean voices telling the story, so a lot of what you are told is through the words of someone sitting in London who hasn’t been here. But I think what irritates me most is the way the media dehumanises people who are in an impossibly vulnerable state, like people dying on the ground. Would that happen in Australia or America of England? Probably not. The media generally applies different rules here.

There are dozens of extraordinary stories that need to be told, that could encourage a bigger international response, stop stigma, remind people where the real outbreak is and reveal the human side to this tragedy. I hope we keep seeing more of that.

What are some of the things that people in Australia may not know about the reality of the Ebola situation?

- Ebola is actually quite hard to catch. Contagion is not an issue until people are symptomatic. Even in the early stages when you are symptomatic, you are unlikely to be infectious for at least a couple of days. Corpses carry the highest amount of viral load which is why so many people have become infected at traditional burials where touching and kissing loved one’s who have died is normal practice.

- In the beginning of the outbreak many Sierra Leoneans didn’t think Ebola was real and blamed the government for using it as a way to make money from the international response, a way for health workers to harvest organs and steal blood.

- Ebola clinicians usually spend about one hour on the ward before it becomes too hot inside a PPE suit.

- Ebola remains in the semen of survivors – so no sex for male Ebola survivors for three months after they recover and test negative.

When Dunlop questioned Abdul, pictured above, what he knew of Australia, he replied, “Oh I know that country very well, my son is there, I haven’t seen him for more than eight years, he went there just after the war. I want to visit him but it’s very hard to get into that country. That guy? What is that guy’s name? The President? I heard about him the other day on the radio, he is not a fine man. He is making these people suffer, these people that go to Australia in those boats.”

What are some of the inspiring stories that you’ve seen of people either surviving or helping to fight the disease?

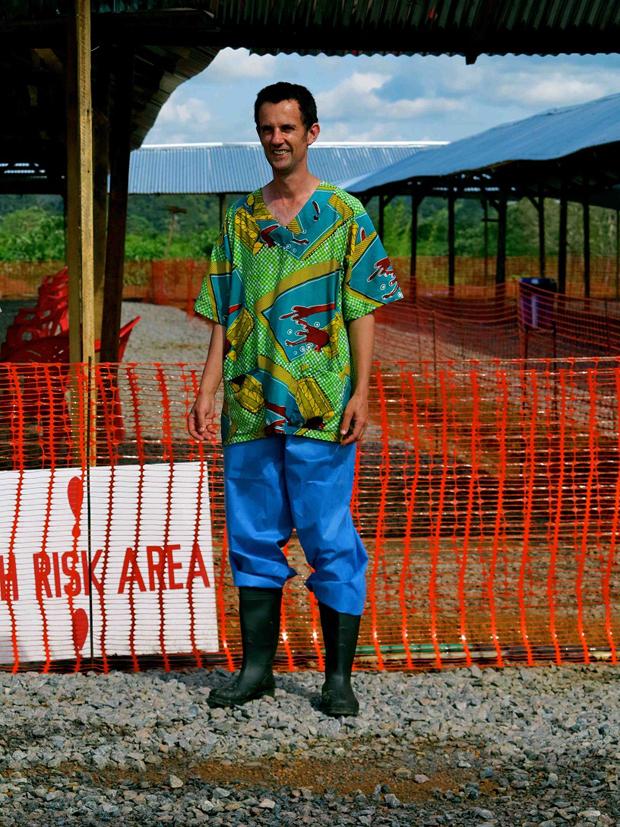

There are so many. I am inspired by any Sierra Leonean health worker who fronts up to an Ebola ward, dresses in PPE (pictured below) and treats patients. They will not be medivaced [medical evacution] if they get infected and have not chosen this situation.

We have a 21-year-old nursing student who turned up to volunteer on the ward after his college closed due to Ebola. The first time he was in a PPE suit he had a panic attack, but he returned the next day and has been showing up ever since, and is now working seven days a week.

I know a survivor who lost 17 family members and has now returned to the ward she was released from to treat patients.

The international team I work with are all volunteers, they are faced with, stress, family guilt and stigma when they return home. But they are so invested in this fight and cannot turn their back on the situation.

There is a group of cleaners I know from Connaught Hospital who do the most high-risk job of anyone – cleaning up highly infectious bodily fluids (vomit, diarrhoea and blood), and washing down corpses. What they see each day is unimaginable. They receive about $50 a week and have been here from the beginning.

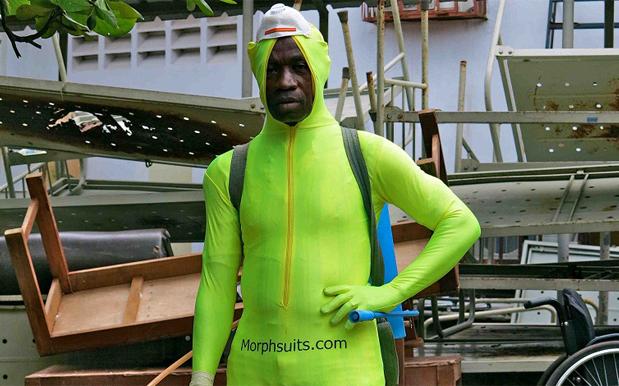

A fumigation officer at Connaught Hospital in Freetown, David Fufana, pictured above, wears a non-regulation morphsuit to conduct his job disinfecting surfaces that Ebola patients have come into contact with.

You interviewed and photographed Juliana, a survivor, on your blog who sadly lost her mother, child and husband to Ebola. Is much being done to help survivors transition back into normal lives and can you give outsiders a sense of what challenges they may be facing?

Yes, there is a new wave of response that is now emerging to support survivors, in Sierra Leone there are over 700 survivors already. Survivors need support to rebuild their life, many have lost their job or have been rejected by their family and community, most have also lost several family members to Ebola. There are now programmes now forming that supports them to rebuild their lives, find work and reconnect with their communities by addressing stigma.

Juliana, pictured above, is an Ebola survivor who wears her late mother’s clothing – some of the last remaining items of clothing in her possession.

You’re from Australia and there’s also an Australian nurse you photographed for your blog. Are there a large number of Australians in Sierra Leone at the moment that you’ve come across and what role are they playing?

There are very few Australians and certainly very few Australian health workers, those that are here work for Red Cross or MSF. The Australian Government’s response has been disappointing. Yes, they donated [an initial] $18 million but what has been expressed repeatedly by authorities on the ground and the Sierra Leonean Government is the need for overseas governments to release health workers.

There was an announcement [last week] by Scott Morrison to suspend processing of humanitarian and immigration visas for holders of west African passports from Ebola affected countries coming to Australia. This makes me hang my head in shame. It demonstrates our government’s complete lack of compassion and understanding of the situation and the disease, and they are clearly using this as an opportunity to create fear and stigma and xenophobia (because we really need more of that in Australia!). The move is just plain racist.

Pictured above is one of the few Australian nurses currently working in Sierra Leone, Marsh.

Lastly with your blog largely focused on fashion – I loved the outfit of the cleaner using the Morphsuit and the handsome African nurse’s three piece hat/shirt/short combo, as well as the custom designed scrubs – what role (if any) does fashion play in the Ebola situation?

Talking about fashion and Ebola in the same sentence seems fairly trite. I guess fashion and style always has a role in peoples’ lives no matter where they are from and what their circumstance. Having a ‘good outfit day’ can lift you up when things feel grim. I think it’s also interesting the way fashion can reflect a mood in a place. I do sometimes feel like there is a clinical look on the streets at the moment. I saw a motor bike taxi driver wearing a pair of isolation ward goggles, I think this is just the beginning of a new trend. I wanted to photograph him but he said “Are you from MSF? I didn’t steal these my friend gave them to me.” He still declined the offer of a photo even though I assured him I wasn’t going to dob him in.

Hassan, pictured above, is a nurse at the Ebola Treatment Centre at Kenema Hospital.