One of the more interesting sticking points of current Coalition Government policy has been their paring back of the previous Rudd/Gillard governments’ (admittedly) wildly ambitious National Broadband Network scheme. When the NBN was originally commissioned, its end goal was to completely revamp Australia’s telecommunications infrastructure network, providing high speed fibre internet directly to the vast majority of Australian homes, in a method known as Fibre to the Premises, or FTTP. When the Coalition Government took the scheme over, the network’s planned outcomes were radically changed to minimise spending, through a pared back rollout involving a Mixed-Technology Method (MTM) which would provide homes with high speed internet via an exchange (similar to the current model) known as Fibre to the Node. The first so-called “independent” Cost Benefit Analysis was released overnight, painting an overwhelmingly positive picture of the financial benefits of the scheme championed by Malcolm Turnbull. But is it all its cracked up to be?

The analysis, known as the

Vertigan Report, hangs its hat on

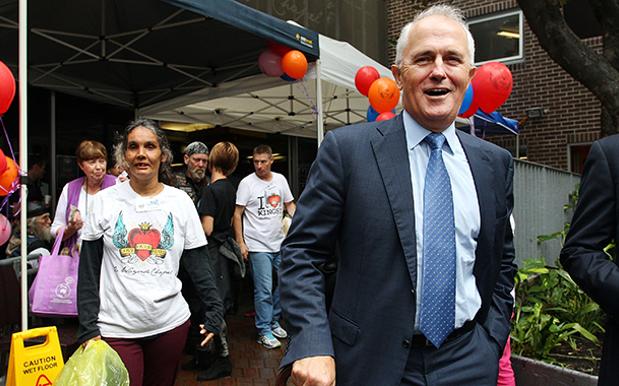

the net economic benefits that a pared back scheme presents to the country at the present time. The basis for this argument is largely the known and established fact that a pared back NBN rollout being orchestrated by the current

Coalition Government will cost less than the fully-fledged, (admittedly) wildly ambitious original scheme proposed by the previous

Labor Government. Nobody will argue against this point, for it is fact. According to the report, the Government stands to yield a net economic benefit of some $16billion through using a pared back scheme. But the report, like everything, is not without its flaws.

Namely, when referring to the scheme’s main benefits in “net” economic terms, the scheme – and Government itself by extension – are needlessly corporatised. Whilst it is the responsibility of the Government to act within their means and provide governance and policy that steers towards a balanced ledger in time, referring to a major national infrastructure project solely on the basis of profit severely devalues the very real societal benefits (or loss thereof) the competing versions of the scheme present.

Additionally, the report glosses over or misrepresents a number of key issues surrounding the roll out of the scheme. Firstly, it devalues the importance, and muddles the priorities of, speeds.

The report uses a bottom-up method of assessing the average Australian’s need for speed, and finds that by 2023, the average Australian household will

require internet speeds of 15 megabits per second. The top 1 percent of households will require 48. The Labor Government’s

Fibre to the Premises plan would have provided connections of 100mbps, upgradable in the future to 1000. The report’s deliberately vague assessment of

Fibre to the Node capabilities stated that it would provide “

Mainly 50-100, some 25-50 and lower.” The report leaves this part vague, because FTTN relies on pre-existing infrastructure, and like pre-existing infrastructure, FTTN connections are greatly affected by distance to the node. An FTTP connection gives each household 100mbps straight up. FTTN relies entirely on how far your house is from a node or exchange.

The report, it should be noted,

stated that it did have access to speed data relative to distance, but it deliberately chose to not include it in its final report. Alarm bells.

Additionally, the report champions the MTM method as being far more “future proof” due to very correct assumption that completing the final upgrade to FTTP in the future would yield lower costs due to the price of the technology required falling over time. What that assumption fails to take into account is that the cost of labour and installation isn’t going to drop (in some cases, double the amount of work will be done for the same end result), the cost of the maintenance and upkeep of existing, ageing copper wiring will remain, as will the cost of replacing sections of failed copper wiring.

The bottom line here, is that this report is – unfortunately – a highly politicised critique of a flawed system, designed as a document aiming to find the question to fit a pre-determined answer. There are benefits to restricting any extravagant spending during a time where economic recklessness could benefit with some temporary reigning in. But restricting innovation is a short-sighted, band-aid option that, in turn, restricts the long-reaching societal benefits associated with a ground-breaking infrastructure project such as this.

Perhaps the real question the Government should be asking themselves is – Do we want things done cheaply? Or do we want them done right?

Photo: Lisa Maree Williams via Getty Images.