As the Ebola crisis worsens in West Africa, the media coverage of the epidemic increases. With things like the outbreak of disease, it becomes quite easy for media outlets to capitalise on people’s inherent fear of illness to further propagate and extend the story. But for all the sensationalism and the like from publishing and broadcasting outlets, it can be easy for the base points of the issue to become lost. So what really is going on with Ebola? Where is it happening? And how can it be fixed? We’ll attempt to wade through the murk and provide you with a basic, clear picture of the key points concerning the biggest health issue the globe has faced in some time.

So what exactly is Ebola anyway?

I suppose this as good a place to start as any. Ebola – full name: Ebola Virus Disease, or Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever – is a disease first discovered in humans in 1976. It is thought to be naturally carried by African fruit bats, and transmitted to humans who have come into contact with bats, or the carcasses of dead bats. Once infected in a human host, it is transmittable human-to-human. The virus presents symptoms in people after an incubation period of anywhere between two days and three weeks. Initial symptoms include fever, sore throat, muscle pain and headaches, which is typically followed by vomiting, rash, diarrhoea, and decreased liver and kidney function. Patients may also begin to bleed internally – and externally in some cases. It is an extremely deadly disease, with fatal cases occurring six to sixteen days after the onset of symptoms, with the primary cause of death being hypovolemic shock (aka low blood pressure due to blood loss).

Yikes. How is it transferred between humans? Like, sneezing and stuff?

Yeah, kinda. Although it should be said here that it’s not a very easily communicable disease, and human-to-human transmission is particularly difficult under regular, Western standards. Its spread in Africa is due to a number of different factors that we’ll touch on in a bit. Basically, it’s only transmittable via direct contact with infected bodily fluids such as blood or fecal matter. And even then it only becomes infectious once a patient begins exhibiting symptoms. It is not an airborne disease.

So where is it all going down right now?

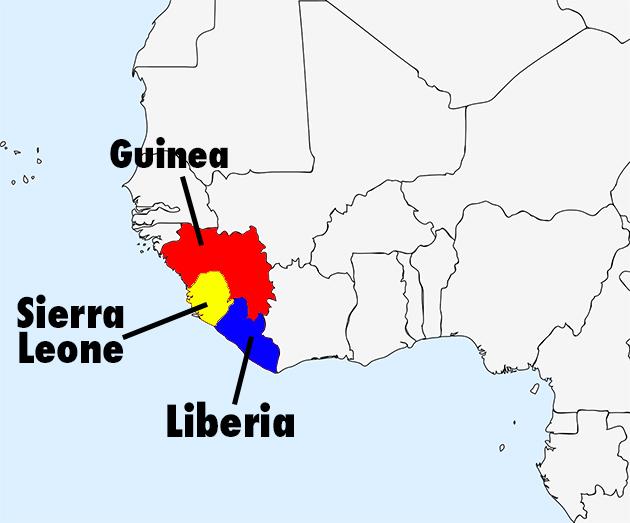

It seems like it’s widespread across the African continent, but the reality is its so far been primarily confined to three adjoining nations in West Africa – Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Here’s a handy map to help you bone up on your geography.

That doesn’t seem like a huge area.

It’s not, in terms of actual land mass. But one of the key factors in this particular outbreak is the fact that all three countries are quite densely populated. For that relatively tiny stretch of land, Liberia has a population of 4.294million people, whilst Sierra Leone has 6.092million, and Guinea has 11.75million – i.e. half the population of Australia in an area of land roughly 1/30th the size.

Whoa! Ok, fair enough. But how did this outbreak start?

Researchers are pointing towards the death of a 2 year-old boy named Emile on the 6th of December last year in the Guéckédou Prefecture of Guinea as this outbreak’s index case – i.e. Patient Zero.

Oh. Poor little guy. How did he get it, and how did it spread from there?

It’s not one-hundred percent confirmed, but experts believe he might have contracted the virus after consuming contaminated bushmeat. After he died, his mother, sister and grandmother all fell ill and subsequently died themselves. From there people who became infected from that initial burst spread the disease to other villages in region.

Hold up, bushmeat? What the hell is that?

Bushmeat is a term that refers to non-domesticated mammals, reptiles, birds, rodents and amphibians that are hunted for food in Africa’s tropical forests.

Holy shit. People eat that?

Yeah, and it’s doing way more harm than good. Not just in terms of getting people sick either – it’s actually considered quite a threat to biodiversity. But people consume bushmeat in these parts of the world as a cultural norm – it’s a cheap and available source of protein. But the problem is that it’s also a remarkably good carrier of a swathe of nasty diseases including Ebola. In fact it’s thought to be the likely initial source of HIV.

The kid ate a bat and got Ebola? Is that how that went down? If so, why doesn’t everyone get Ebola?

Much in the same way that everyone who eats chicken doesn’t cop a dose of salmonella or e-coli, people who prepare or eat bushmeat only cop diseases when it’s been contaminated by infected blood, or been improperly prepared.

So it’s like a really gnarly case of food poisoning?

That’s kind of a harsh way of looking at it, but it’s more or less the same principle, yeah.

How bad is this current outbreak?

In short, worse than every other recorded outbreak of Ebola combined. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention have, as of October 15th, put the number of cases at 8997 with 5006 of those laboratory confirmed. Of those 8997, a total of 4493 people have died from the disease. But officials at the World Health Organisation have warned that due to non-reporting in the region, the actual number and fatality rate are in actuality a lot higher than then number they can reliably report. The warning they’ve given is that the actual fatality rate for this particular outbreak is somewhere in the vicinity of 71%.

That’s horrifying. How has it spread so much if it’s hard to contract?

There’s a number of factors influencing the spread of the disease through this particular region, but the primary one comes down to Government destabilisation. The region – particularly Sierra Leone – has just come out of a long and particularly nasty period of civil war and unrest, and the borders between the three countries are porous at best, containing high traffic trade routes between densely populated regions of each of the three countries. The lack of Government control has meant that general health in the region has been under the watch of humanitarian organisations like Doctors Without Borders. Whilst they’ve done exceptional work in the area, particularly with war-related injuries and issues arising from poverty and malnourishment, the lack of singular, centralised, bureaucratic control renders any preparation efforts for containment and prevention of an Ebola outbreak scattered and inefficient at best.

On top of that, there’s cultural death customs that are adding to the spread of the outbreak. The bodies of the deceased remain extremely infectious, but local customs call for a lot of physical contact with the dead, including the washing of bodies. Without soap and running water in ready supply, this practice becomes a veritable lightning rod for transmission.

Finally, a lot of the hospitals in the region are ill-equipped and understaffed, leading to a huge amount of care and aid workers contracting the virus themselves. In fact, the WHO estimates that around ten percent of the total fatalities have been health care workers.

Has it spread outside of that region at all yet?

A little, but it’s been largely contained. Spain and Senegal have both seen 1 non-fatal case each, whilst the United States has now seen two human-to-human transmissions following the death of its first Ebola patient in Dallas. The two people that contracted Ebola from the initial case were both nurses who cared for him. The transmission has been blamed on “a lapse in protocol” and are now being stringently quarantined and monitored.

Didn’t one of the US cases fly on a plane before they were diagnosed?

Yeah. Let’s just chalk that one up to a flailing US medical system being a bunch of dingbats. This is what happens when you try and halt Obamacare, or something like that.

So are they the only other places its been?

Actually, no. The biggest outbreak outside of the original hot spots has been in Nigeria. But despite the usually scattered systems that they have in place, the country has been able to largely contain it. Out of only 20 cases seen, 8 people have died. So there’s irrefutable proof that African health systems, when properly implemented, do have the ability to contain and halt the spread of the disease – even in densely populated areas.

How on earth did they manage to do that?

Money. Money and resources. Some of Africa’s richest people reside in Nigeria – including Africa’s richest man Aliko Dangote. They recognised quite early the threat Ebola poses to the region and poured in the resources necessary to stop it. Nigeria is now on the cusp of being declared Ebola free as a result.

So how long would it take to stop Ebola in the affected regions?

The World Health Organisation suggests that this outbreak could be totally contained and eradicated within six to nine months. But it’s also warned that the window for serious containment efforts to get underway is rapidly closing. Within 60 days the epidemic could become a full-blown catastrophe, and it’s estimated that around 10,000 new cases could be presenting per week by December.

What’s needed to stop this outbreak?

Money. Money and resources. International aid from richer countries, personnel and resources, skilled aid and health workers. A huge effort will be needed to reign it in, but it is – for the moment at least – entirely doable. The Australian Government has pitched in $18million – shy of Mark Zuckerberg‘s individual donation of $25million – but refuses to send local aid workers and troops.

Is there anything I can do to help?

Glad you asked! You can donate whatever you can to a number of different aid organisations helping out in the region.

What are the chances of me getting Ebola?

That all depends. Are you planning on travelling to West Africa to either help treat Ebola patients or eat bushmeat anytime soon?

…no.

Then sitting in your lounge room in Australia should be all the protection you need from it. Beyond someone physically bringing it in to the country, the likelihood of an outbreak here is extremely low. And even then our medical systems are well equipped to isolate and contain the virus.

But that doesn’t change the fact that the issue is a very dire one, and requires everyone’s attention and efforts in order to contain and eradicate the outbreak.

The virus is extremely dangerous, and is a nasty, needless way to die. It’s already destroying families and communities, and has the potential to cripple entire nations.

If more isn’t done – and more has to be done – quickly, the situation could spiral wildly out of control and become very, very grave indeed.

Photos: Zoom Dosso, Matt Cardy, and John Moore via Getty Images.