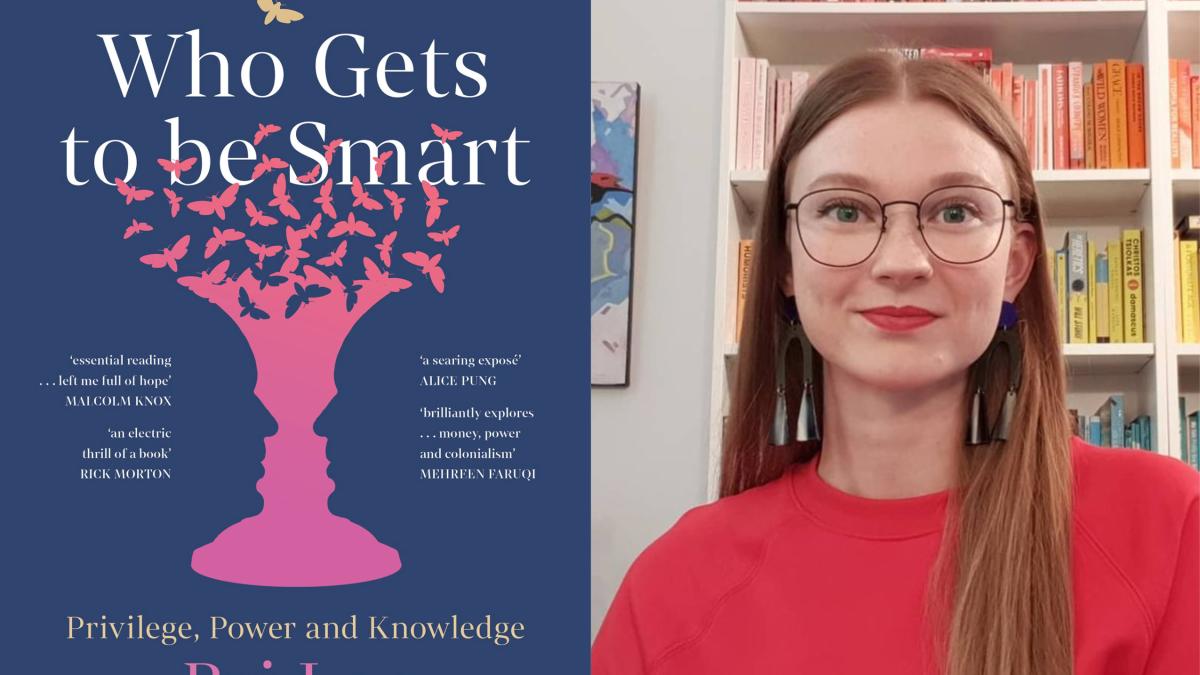

Bri Lee‘s third book, Who Gets To Be Smart, made me feel dumb as hell – in a good way. I know that sounds silly, but this book was a masterclass in unlearning old ideas about my education that were ingrained in me from a very young age.

Who Gets To Be Smart is a timely exploration into class and privilege in Australia, particularly when it comes to education. It makes you – it made me, at least – take a very hard look at our schooling system and ask questions like:

Why is Australia the fourth-most segregated-by-class schooling system of all OECD (The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development) nations?

Why do boys do better at coed schools, while girls do better at single sex schools?

Who controls the curriculum and why?

PEDESTRIAN.TV spoke to Lee about her new book, here’s what she said.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

PEDESTRIAN.TV: Why did you choose to write about education?

Bri Lee: The catalyst really was what people will read about in chapter one, when my friend Damien got the Rhodes Scholarship [University of Oxford].

So that happened a few years ago and at the time he got that news – of course I was, you know, thrilled for him and very supportive. But also, I felt just sort of punched in the gut. Because I had really been outsourcing my priorities to these institutions. And I feel like everything I’ve been told at school and then university was that winning a scholarship, like that, made him the winner and me a loser.

So then when I went over to visit him and I took that tour of Oxford and Rhodes House, and I started getting a bit critical, and asking some questions about where the money comes from, and where the money keeps going. That was one thing. But then when I came back to Australia, and started looking at our institutions here, and I realised we were just as bad if not worse, in some ways, because we’re a good little colonial outpost – that was when I started wanting to write something bigger about it, you know, about how those terrible ideas are still very much alive and thriving in Australia.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CPkaUTogTy-/

PTV: And did you know a lot about the education system before beginning your research?

BL: No, not at all, barely anything. And I was shocked to read a lot of what I found. And I guess that’s been the case with all of my books so far that I sort of just write it, and that reader I have in mind is just who I was when I started the book.

When I go back and edit it several times before sending it to my publisher I’m often, sort of embarrassed or I cringe about what I thought and felt at the beginning of the book.

And so far, with all three of my books, I feel myself and my opinions have been quite radically altered by the end of it compared to where I was at the beginning. And so I guess, ideally, I hope that readers feel like they go on that journey as well.

PTV: Can you talk me through your findings about how boys do better at coed schools and girls do better in single sex schools?

BL: I think it’s important to draw attention – the way in which girls do better at single sex schools is actually in their lack of self confidence and their ability to accurately estimate how well they’re doing, in particular for subjects in the STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] area.

And what the research shows is that boys’ increased confidence in their own abilities actually translates to better results. And the reason I’m trying to be really clear about what that research actually shows is that – it shows how we are still letting girls down by teachers and adults and the way they treat them, the way they make them feel about themselves.

And then that does translate into actual academic results. And my position is that a young person feeling comfortable in their own skin, and confident in themselves, is just as, if not more important than their academic results.

And I think we need to ask ourselves some really tough and hard questions about why girls at coed schools don’t feel as confident in themselves. And then also ask ourselves hard questions about why we’re so obsessed with their grades instead of their sense of self.

PTV: Were you surprised by those findings?

BL: It’s a kind of – not an urban legend, but it’s like a prevailing wisdom, I should say, that’s sort of been floating around for a long time – that girls do better on their own. But I’d never looked into why, and how, and sort of what the causes are.

And it is interesting that there are fewer boys-only secondary schools, there are far more girls-only secondary schools, which sort of supports that kind of prevailing wisdom or that presumption that people are much more keen to send their girls to girls-only schools than they are to send their boys to boys-only schools.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CPKdbEst-0A/

PTV: There is a part in your chapter on schools where you equate effort with privilege, where you criticise the common saying, ‘If I just put in more effort, I would’ve done better.’ Could you expand on that?

BL: Yeah, I just don’t think it’s quite as simple as that. What I was trying to do with the book is ask some questions about ideas of ‘deserving’. You know, this idea that anyone – if you work really hard, then you deserve the results when the fact is that some kids go to school pretty hungry. And when they come home, they have caring obligations, or they have to go to a part-time job.

Other places in the world don’t even have homework, because homework can exacerbate the difference between one kid who can go home and have a parent that can help them with their homework before they sit down for dinner together, compared to another kid who has to care for siblings or care for parents or go out and earn money for their family.

I don’t think it’s as simple as rewarding effort while we have these strong socio-economic currents in play the way we do that don’t give every child an actual equality of opportunity.

PTV: To wrap up, I thought I’d ask you a question you ask in the book: what is the purpose of a school?

BL: What I wish every school did, to which I guess translates to what I think the purpose of the school should be, is to give every child an actual equal opportunity to reach their full potential.

And what that means specifically is that if a child turns up to school without having had breakfast, the school is the perfect place to be able to provide their child with breakfast before you throw them into a classroom with 30 other kids all of whom have full bellies.

Regardless of where an individual considers their politics fall, in terms of whether they want equality of opportunity or equality of outcome, I think we can agree that there is equality of absolutely nothing when we live in a country where 20 per cent of five-year-olds are not meeting their developmental milestones before they start grade one.

The point of a school is to put the best interests of children first, and that is not what is currently happening across the board in Australia.

Who Gets To Be Smart: Privilege, Knowledge, and Power by Bri Lee is available now wherever you buy your books.

While the crux of our interview focused on the education system and its failings in Australia, that’s not all Who Gets To Be Smart is about. It also delves into language, colonialism, and the Black Lives Matter movement in Australia

Litty Committee is Pedestrian.TV’s twice-monthly book column. Every month, we’ll take you through the newest reads and spotlight a novel we think you might like.

You can catch up on our other Litty Committee recommendations here.