And with social media constantly assaulting us, those huge stories were delivered to us instantly, rendering the breaking news element of newspapers virtually useless. Seriously mate, <3 u, internet.

But duh, you already know this. After all, you’re reading a site employed with people (hey, me! *waves*) that could barely have had the job titles we now do even ten years ago. News is arguably best consumed online – efficiency and the ability to ~join in on a conversation~ is tending to beat the price of ink smudges on your fingers and extra recycling.

But what often overshadows a news story is what some keyboard-warrior flurry quickly digests into an all-purpose hashtag – case in point, this month’s #JeSuisCharlie. Waxing lyrical over this so-called hashtag clicktivism (or “hashtivism” or whatever mouthful of a word you like) is by no means new, but what will it look like in 2015? Should we be swept up in the peer-pressure of hashtags that might seem well-meaning on the surface, but are actually one-dimensional and reductive? Or more realistically, not really that useful?

One of the biggest hashtag clicktivism campaigns of 2014 was #bringbackourgirls, a tag spawned to generate greater news publicity over the Boko Haram abduction of 219 Nigerian schoolgirls, an absolutely harrowing news story that was widely considered to have wrongfully slipped from front pages worldwide. And so the hashtag spread like wildfire, from Michelle Obama to Malala Yousafzai.

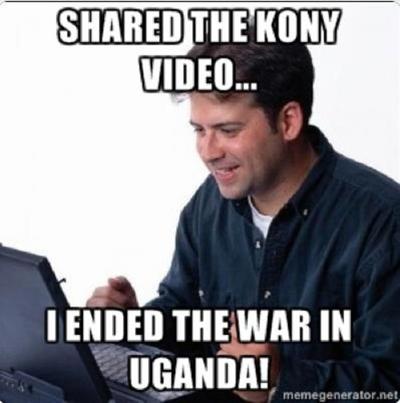

And, of course, so it should. A story of such immense tragedy deserves all the attention it can possibly get, so humanity can band together to try and squeeze something good out of a terrible situation. Sharing the tag on twitter and facebook was important, because it drew eyes around the world to an issue that could have been left in the dark. While the #bringbackourgirls campaign was in fact started by Nigerians, the movement was swept up and elevated by outsiders abroad. The cynic here could look at this bandwagon style support as relatively apathetic, but exposure in these kind of cases tends to put pressure on taking action: despite all the flack it received, the #Kony2012 movement spurred a 5,000-strong military procedure attempting to finally quell Joseph Kony’s horrific activity.

Never mind those that support blindly; sometimes this stuff works.

What’s so difficult to swallow about hashtag clicktivism is that it is inherently fleeting — a hashtag such as #bringbackourgirls or #MH370 might trend well on social media for weeks, gathering up those who mean well in its wake. But hashtags ebb as new trends flow. The Nigerian schoolgirls have still not been found, but the supporting hashtag has all but disappeared. The Malaysian Airlines flight is still a mystery, but coverage has become scarce. “The most important thing…is to keep the conversation going,” Jacquita Gomes, whose husband was aboard the doomed MH370 flight, told The Guardian, encouraging continued support online and in the media.

France was truly rocked to its core at the beginning of January with the tragic terrorist attack on the satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo, killing 15. The tag, #jesuischarlie rapidly emerged, acting as a symbolic, defiantly-raised fist to acts of terror. Millions quickly jumped on board to support the campaign on social media and in vigils worldwide, and it boldly held the unwavering focus of virtually the entire world.

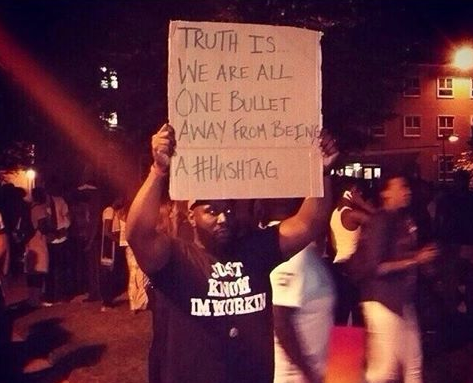

Events such as the Charlie Hebdo attack, the Ferguson unrest and the Sydney siege all drew a widely-spread social media hashtag within hours, or even during, their respective events. However, what’s ultimately more poignant in looking at hashtagivism is what doesn’t get a hashtag – the stories that are laid to the wayside without overwhelming coverage and support.

Case in point: the utterly confounding massacre in Nigeria a few weeks ago by Boko Haram – an attack that has left a reported 2000 civilians killed. Where is the furore? Where is the hashtag? The lack of attention is heartbreaking.

But srsly, WHY? When the Charlie Hebdo movement gained so much momentum online, it just seems like some sort of 404 – error that the Baga tragedy didn’t have a strong hashtag following. Because labelling an event with a hashtag has become so ubiquitous, any event that doesn’t get the same recognition can dangerously slip from the public eye. We’re doing this to ourselves, but it truly blows.

The Baga massacre in particular may have been overlooked online for two big reasons, in my opinion: firstly, news reporting the attack trickled in mostly on January 10 – two days after the Charlie Hebdo attack. After two days of being glued to the dramatic events that unfolded after the attack, it was seemingly difficult to redirect the world’s attention to Baga. It’s absolutely no excuse, but when the world is already experiencing a bad news week, it’s difficult to swallow another tragedy. Adding to that, the news coverage on Baga, unlike Charlie Hebdo, was not immediate, due to limited resources and frequent internet blocks, so on-the-ground rolling reports and citizen journalism have not been as easy — unlike Paris. Updated information on the massacre has just not been able to meet the internet’s rate of consumption.

Secondly, the largely Western-based and led social media movements — which in turn virtually dictate what news outlets report on — will react and develop differently to attacks that could conceivably be carried out on their own soil – in other words, the fear perpetrated by certain news stories can effect its social media campaign. The Charlie Hebdo attacks bore a sentiment and reaction similar to the recent Sydney Siege; Australians could, arguably, empathise profoundly with the pain France was enduring. It’s a “if it could happen there, it could happen in my own city” complex which is understandable, but damaging.

The Boko Haram massacre was overwhelming in scale – the kind of attack many Western social media users could hardly extract a similar response of ‘fear’ or ‘threat’ to. It’s a tragedy many Westerners will feel detached from, but an extreme tragedy nonetheless.

But really, you can’t help asking WHY at the potential of something like this falling through the cracks of the media.

You can easily be critical of hashtag activism – after all, hanging up your finger after a long day of retweeting hashtag-based movements surely doesn’t deserve a pat on the back, or even the term “activism” at all. But nonetheless, 2015 will be undoubtedly rife with big news stories being trailed with hopeful #PithySayings designed to spark change.

But when causes are remote, and when participating in actual news-stopping protests just isn’t possible, raising a hashtag salute is a pretty easy and harmless way to show your solidarity.

It’s obvious as hell that simply sharing a hashtag will not make you a philanthropist, but there’s been causes out there that actually garner positive change from the swells of becoming an online trend. In 2010, the horrific earthquake in Haiti was rapidly taken under the internet’s wing – the #HaitiRelief hashtag encouraging donations to the Red Cross reportedly helped raise $8 million. If that isn’t strength in numbers, I don’t know what is.

The Haiti movement wasn’t a rarity, of course – last year’s ALS ice bucket challenge, as vain as it often was, raised over $100 million in just 30 days. It’s staggering, and makes every hashtag activism critic’s argument seem weak. One hundred million dollars.

If we look to the case of Daniel Pierce, a gay American teenager who was “disowned” by his family, it seems that- much like the ice bucket challenge – if those who use a hashtag are given a follow up step (in Pierce’s case this was a crowdfunding page to raise money after he was kicked out), like direction to donate to a good cause, the principles of hashtag activism flourish. The more specific and more spoon-fed the cause a tag supports is, the more effective it will fare.

So If 2015 looks less like #jesuischarlie retweeted en masse without thinking, and more like the game-changing #illridewithyou, #HaitiRelief or #DanielPierce, this year will be huge.

Lead image by Michael B. Thomas via Getty.