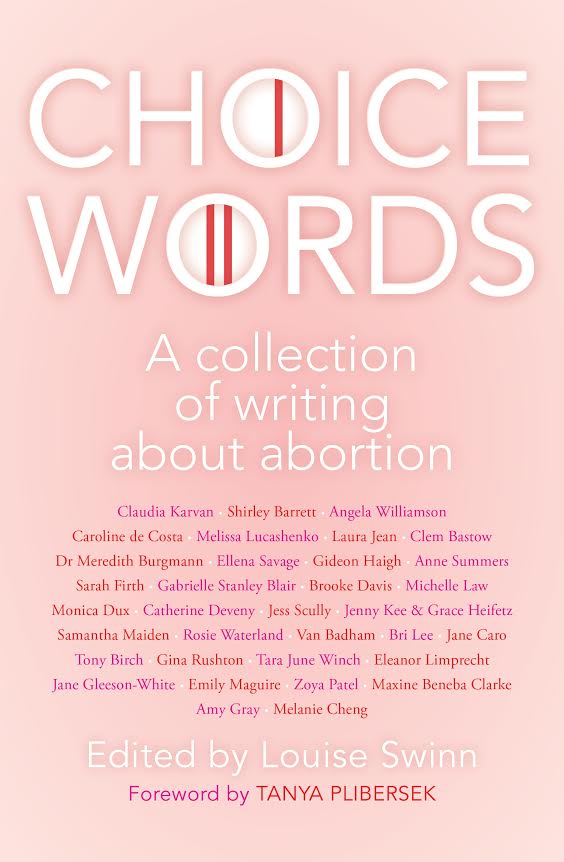

The following is an excerpt from the book Choice Words: A Collection Of Writing About Abortion edited by Louise Swinn and published by Allen & Unwin. You can buy a copy here.

I didn’t choose to get pregnant when I did, though I was complicit in the choice in that I chose to have sex that night, I suppose, in the mangled way that sometimes happens with a person you have not planned to have sex with and probably won’t again, and I chose to have it in such a way that made possible a slippage of fecund biological material from one place to another, though in all honesty I thought that the person I was with would not be so careless or cruel as to endanger me in that way, and I chose to imbibe the several drinks that led me to this somewhat unglamorous affair. I did not choose the patriarchal condition of normative heterosexual hook-ups whereby the primary form of eroticism is the careless penile penetration of women and woman-shaped people in pursuit of male orgasm regardless of the risk of disease or pregnancy, but I did choose to exercise in my warped way my puny young girl agency to objectify and ‘fuck’ guys with the aim of reversing the ways in which I had been fucked and fucked over by them.

I didn’t choose to be too broke to pay the out-of-pocket for the abortion anaesthetic, which at the Royal Women’s was $140, and I didn’t choose the character of the girl I was seeing at the time though the character of the girl I was seeing at the time was what had endeared her to me, and while I did not choose for her to pay for the anaesthetic, she did it anyway, because that was her character, and while I was getting my guts pried open the girl napped on her rolled up leather jacket like a sweet punk-rock baby in the barren chamber of the hospital and for this she is due my eternal gratitude.

I didn’t choose to have zero emotional after-effects of that abortion, though I felt as though I couldn’t mention this too often or too loudly in case it seemed in some way to trivialise the emotional after-effects some others experienced after their abortions. More trivialising is the dominant cultural narrative I choose now not to abide by, the narrative of inevitable future shame and regret pre-post abortion, as though a feeling of regret is worse than a lifetime of poverty or being eternally tethered to a man you hate or being dependent for years on a biological family you wish to be separate from, or simply being forced to do something you instinctively don’t want to do, well. I regret a lot, believe me: I regret my poor food choices and my poor work choices and I regret being born with the biological equipment that bears the burden of poor sexual choice-making under the influence of alcohol at age twenty. But in no chamber of my soul is there an inkling of regret at ending a pregnancy I did not want and if I hadn’t had the legal choice to end it at the Royal Women’s I’d have done it anyway, I’d have rolled down a flight of stairs, I’d have seen a dodgy doctor, I’d have drunk poison, I’d have done it all, and I might have died trying.

Because this is what agency is; it is doing what you can do with the circumstances you are dealt. It is choosing to do what you need to do even and especially when your mother or your superego disapproves. In my opinion sex is not a sacred jewel and poor erotic decisions are not something I need protection from and motherhood is not holy. In my view, motherhood is a practical economic matter and any effort to pair femininity with maternity with biological destiny with virgin births with earthy crystal-lovemaking is an effort to relegate the female form to a position of inferiority, to a state of constant need and gratitude and dependence.

Julia Kristeva writes that the ‘virgin’ of the Virgin Mary was in fact a mistranslation of an ancient Semitic word for unmarried young woman. Conflating ‘virgin’ with ‘unmarried young woman’, she says, erases the young mother’s extra-patriarchal jouissance, evidence of her bodily joy and her sensual desires, and subsumes it under the sign of the male-controlled ‘virgin’. The mistranslation is said to strip pre-Christian societies of their matrilineal inheritance rites and it strips Mary of her agency, too – her scampish, light-filled, unwed spirit – and replaces it with the sign of the father.

In other words, if the Virgin Mary had more correctly been named the Unwed Teen Mum Mary, we who inherit the moral framework of the Christian tradition might not feel compelled to trot out evidence that our access to abortion is a moral good in that it is a material good in that there can be no moral good without humans exercising their agency in whatever puny ways they can, like having a son named Jesus. Or just not.

Sexuality and impurity might not be coupled. Maternity might be understood as just one of the many ways a person can choose to belong to time rather than a duty women with wombs have, to tip themselves completely into the service of others.

It is true too, however, that we who have inherited the moral framework of the Christian tradition have inherited a limited set of tropes through which we understand what a body is and what a gender does, and from within this fog we find it challenging or perhaps inconvenient to look upon the full force of the animal urges that course through us all. The animal spirit that offers recourse to say no, to say I will not abide, to say I will choose the smallest thing that has been offered to me, to protect me, to protect the others whose tender red organs have been taken, in name and in law, from them.

At twenty, I did not want to be someone’s mother. At thirty, I have been all kinds of mother: I have paid the rent for rockdogs, I have made more meals than have been made for me, I have poured out more love than has been poured into me, I am practically a saint – but no one tells me that, not enough anyway – and I am trying again to choose to not do that, to not be a mother.

Instead I’m trying to see that my tender red organs and the few dollars I earn and the words that I say and write are truly mine and that I’m therefore responsible for what I do with them. Sheila Heti writes that the hardest thing for a woman to do is to choose to not become a mother and while the hardest thing is not always the best thing, I am curious about a life where choice is more rigorously available to me and perhaps the first choice to make is the choice to take my agency, take it, make it mine.