There’s no denying that Australian Survivor Season 10, Heroes vs Villains, has provided some thrilling entertainment. Definite highlights have been Benjamin Law and Paige Donald’s ground-breaking challenge win by communicating through Auslan, George Mladenov’s increasingly unhinged mind-games at tribals, and Liz Parnov’s endurance in winning the final challenge and her unanimous Sole Survivor win. But we’ve also seen some of Survivor’s tendency to reproduce Australian’s special brand of overt and casual racism.

This season, we saw all of the three Asian players – Mimi Tang, Stevie Khouw, and Ben – swiftly relegated to the bottom of their respective alliances and labelled as “suss”, “shifty”, “silver-tongued”, “sneaky” or “a snake” by the white majorities, invoking (unconsciously or not) old, racist anti-Asian tropes — further insulting because the game itself is literally predicated on lying, strategy and subterfuge for individual survival.

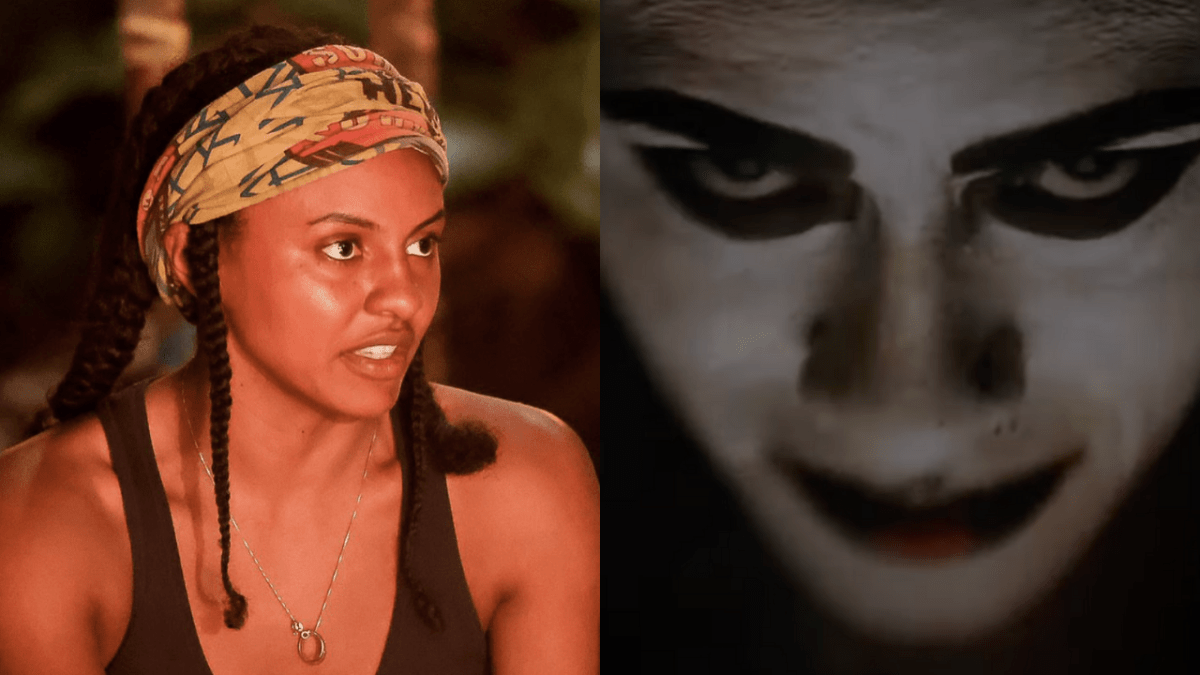

We also had to endure an extraordinarily blatant, but casually delivered racist moment of dialogue. In the opening episode, white player Rogue Rubin stated that she was “more African American” than the only Black woman in the cast, Nina Twine — to her face. Rogue said this because she was born in South Africa and worked in the States.

Yep, wow.

This white woman on Survivor just told a black woman to her face that she’s more African American than her… 😬 #SurvivorAU pic.twitter.com/TCkXXC4Cru

— Jordan Woodson #TheKillerSweep (@jordanjwoodson) January 30, 2023

It’s difficult to imagine such an obviously outrageous comment passing without challenge on the American Survivor franchise, especially given that Nina is a Black woman from North Carolina, a state with a deep legacy of racial trauma and slavery.

As disappointing as these incidents are, a more fundamental and pervasive component of race and superiority within Survivor that struck me more deeply this season was its sustained erasure of indigeneity, culture and Country.

I am certainly not the first to point out the international Survivor franchise’s problematic (to say the least) appropriation and mish-mash of African, Asian and Pacific cultural symbolism, terms and icons – and this season has certainly been no different.

Season 10’s introduction montage is set to Survivor’s iconic but culturally ambiguous theme song, and features recurring motifs of silhouettes of men swinging weapons by torch light and a person in white and black face paint staring menacingly at the camera.

We take it that the brave, muscular contestants – or “castaways” as the show calls them, probably in reference to 300 year old “colonial fairytale” Robinson Crusoe – are entering a beautiful but primitive, dangerous environment governed by tribal rules and rituals.

Almost as soon as it aired in 1999, scholars and media critics have commented on the Survivor franchise’s inherently colonial relationship to land and its tendency to erase the Indigenous cultures of the locations where it’s filmed. One legend from Sydney even wrote a thesis about it.

Survivor bombards its audiences with exotic-but-primitive aesthetics; it’s hard to put a finger on where you’ve come across similar images or symbols before, but the audience knows they’re not from the West. Examples include “tribal” names and adornments, player’s torches, tribal council sets, and immunity idols featuring bones or teeth. Designs of these vary season to season, but rarely (if ever) do they speak to or draw from the local culture of the setting.

Beyond the player-chosen merged tribal name Fa’amolemole, Australian Survivor season 10 does not appear to explicitly honour or acknowledge Samoan culture as it returned for the first time since 2017 — despite the fact that throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Samoa was subjected to the control and power struggles of colonial powers Britain, Germany and the United States.

Survivor’s cultural erasure and colonial relationship to land was no more apparent in the somewhat unique circumstances of Australian Survivor seasons eight and nine (aired in 2021 and 2022), which were filmed domestically due to COVID-19 and travel restrictions.

Survivor producers are generally coy about the precise location of each season, but a little research revealed the 2021 season was filmed in on Kalkadoon and Mitakoodi Country, near Mount Isa in western Queensland. Season 2022 was filmed on Gudjula Country near the town of Charters Towers, close to Townsville.

Beyond a cookie-cutter single slide at the beginning of each season and accompanying Instagram post acknowledging the respective Traditional Owner groups, Aboriginal culture was not incorporated in the show at all.

casting really said: oh you wanted diversity? here’s a big game hunter, a racist and an anti-lockdown clown #SurvivorAU

— liz burn it all down party💅🏻 (@teamshonee) February 13, 2023

It was disappointing — but probably not surprising for fans of the international franchise — that producers of Australian Survivor Endemol Shine chose to regurgitate the global franchise’s patchwork of cultural appropriation rather than take the opportunity to showcase the world’s longest continuously living cultures.

Instead, Australian Survivor presented the western Queensland outback as a harsh, dangerous, and most importantly uninhabitable and uninhabited landscape.

And yes, I know, as with any reality TV hit, we accept a veneer of unreality, so as viewers we can be sucked into believing the contestants are truly isolated, but really we know that the crew’s camp or a town is never that far away.

However, in the Australian context, pretending the contest takes place in a nameless and people-less landscape is even more problematic.

The Kalkadoon, Mitakoodi, and Gudjula people were living healthy and sustainable lives on their respective Country for thousands of generations. British colonisers used the legal fiction of terra nullius to justify assuming sovereignty over the Australian continent, claiming that the land was uninhabited.

So, for an Australian reality series to be produced in 2021 and 2022 with virtually zero acknowledgment of Indigenous Traditional Owners and cultures of the land they shoot and compete on is essentially erasing them again.

Respectful and responsible cultural consultation and inclusion can be initially hard and uncomfortable for non-Indigenous people conducting business in Australia. It requires fair compensation for time, emotional labour and use of Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property. But when Australian TV producers make the effort and move beyond simplistic representation or inclusions of Blak contestants, they can craft takes on globally successful media that can’t be done anywhere else.

As Benjamin Law and Australian Survivor host Jonathan LaPaglia have pointed out, increasing the cultural diversity of contestants — as the US franchise has recently committed to — would be a great first step.

But really, more than 20 years into Australian Survivor (and 44 seasons in the US), the franchise needs to sort out its cultural appropriation and colonial fantasy bullshit.

Survivor will be just as thrilling without a bunch of made up and appropriative set dressing and tribal imagery.

Massimo Amerena is a settler living, learning, working and consuming TV on Wurundjeri Country. You can read more of his work here.